Sixty years after the Cuban Missile Crisis, how to face a new era of global catastrophic risks

This month marks the 60th anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis. For two tense weeks, from October 16 to October 29, 1962, the United States and the Soviet Union stood on the brink of nuclear war. Sixty years later, tensions among the world’s greatest militaries are once again uncomfortably high.

In recent weeks, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s nuclear-laden threats to use “all available means” in the Russo-Ukrainian war have raised the prospect of nuclear war once again. And on Oct. 6, US President Joe Biden reportedly told a group of Democratic donors, “For the first time since the Cuban Missile Crisis, we have a direct threat to use nuclear weapons if things actually continue as they are.” I was on my way.”

Any uncontrolled escalation of these existing conflicts could result in a global catastrophe, and the history of the Cuban Missile Crisis suggests that such an escalation may be more likely to come about through miscalculations and accidents. Nuclear near miss lists show the variety of routes that could have led to disaster during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Famously, Soviet naval officer Vasili Arkhipov vetoed a nuclear submarine captain’s plan to launch a nuclear-armed torpedo in response to depth charges fired by US forces, which proved non-lethal. Had Arkhipov not been on that particular ship, the captain might have had the other two votes he needed to order a launch.

Today, artificial intelligence and other new technologies, if used carelessly, could increase the risk of accidents and misjudgments even further. For example, imagine a repeat of the Cuban Missile Crisis with Arkhipov replaced by an AI-enabled decision-making tool. At the confluence of rapid technological advances and heightened fears of a major war involving the great powers, it is easy to throw up our hands and dismiss global catastrophe risks – including but not limited to the intersection of artificial intelligence and nuclear weapons – as inherently unsolvable to watch. However, history also shows that policymakers, scientists and ordinary people can come together to reduce global disaster risks. There are simple steps we can take today from the brink: developing new confidence-building measures on AI, updating nuclear risk reduction tools like the nuclear hotline, and resuming backchannel dialogues between non-governmental contacts in the United States and Russia and the United States and China.

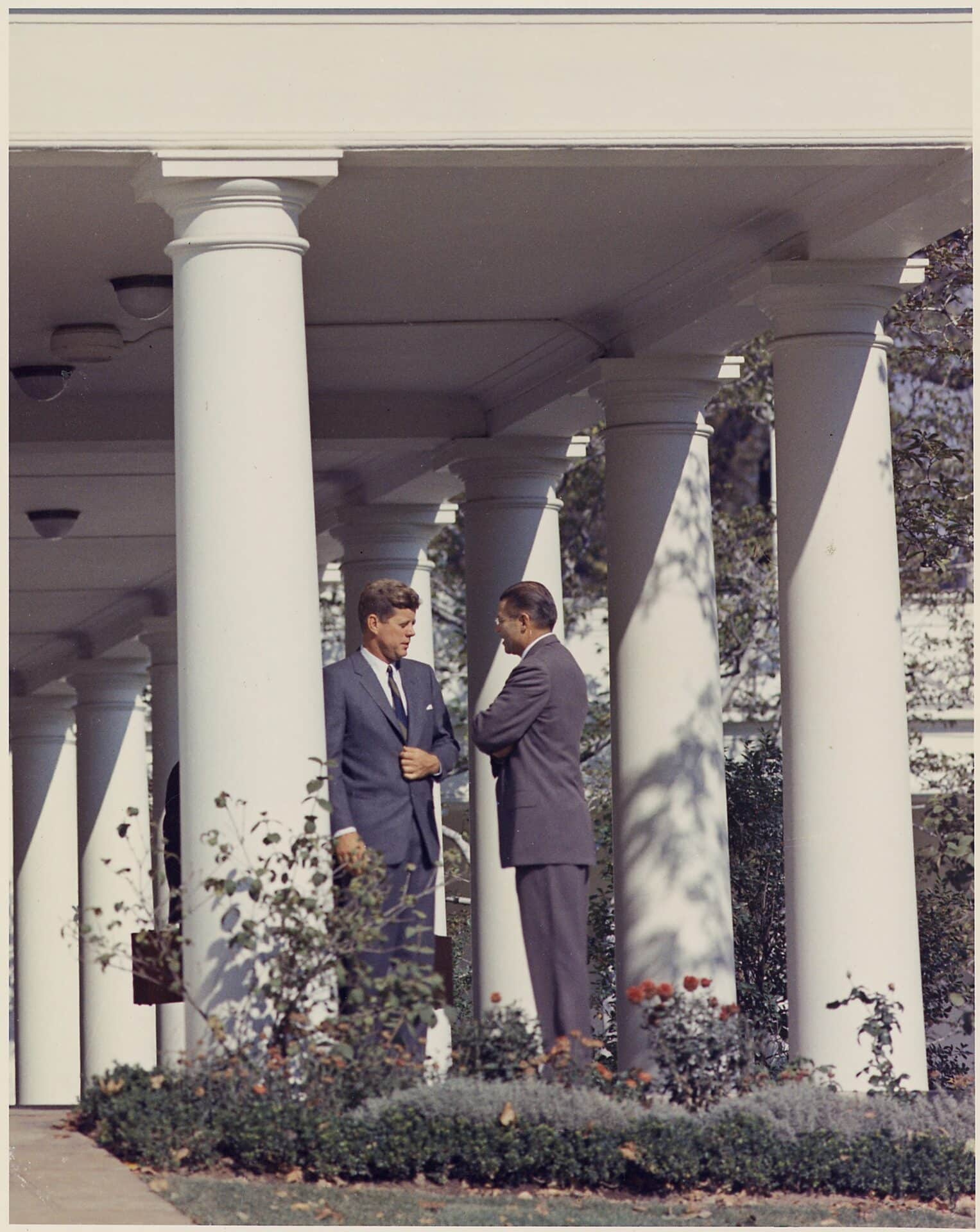

New twists on old problems. The generation that experienced the Cuban Missile Crisis is shrinking. For example, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken was just 6 months old when President John F. Kennedy learned that U-2 spy planes had detected Russian ballistic missiles stationed in Cuba. For those who remember her, the following 13 days were a time of deep awareness of the fragility of humanity.

Born in post-Cold War Germany in a reunited Germany, like most people of my generation, I had no direct experience of nuclear crises until Russia invaded Ukraine. NPR interviews with two women who lived through the crisis offer a glimpse of the experience. One, then a kid in Miami, “didn’t sleep for days” and was “very scared.” The other in Cuba felt that “the world was going to end”. Her lived experiences show that even small-scale interventions in global disaster risks can have very real impacts on the mental health and well-being of people around the world.

Today, the US and Russian nuclear arsenals are smaller than they were in 1962, but technological advances have introduced a new element of uncertainty. The widespread adoption of AI in military technologies, including the use of autonomous and near-autonomous weapons, may introduce new risks: increased warfare velocity, automation bias, and other risks related to the brittleness and documented failure modes of machine learning systems. To understand this, imagine a 21st century Cuban Missile Crisis with artificial intelligence. AI and international security expert Michael C. Horowitz — a professor at the University of Pennsylvania and now director of the US Department of Defense’s Office of Emerging Capabilities Policy — has examined what the blockade of Cuba looked like with widespread deployment of AI-enabled ships could . (Full disclosure: I used to work for Horowitz at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perry World House.)

Not all AI applications are destabilizing, as Horowitz explains, and “in a crisis that could end in global nuclear war, relinquishing human control to algorithms would require extremely high levels of perceived reliability and effectiveness.” Rather, problems arise occurs when the perception of reliability and effectiveness does not correspond to reality. For example, the speed of AI-supported decision-making could compress a two-week crisis into two hours. That may leave no time for a future Arkhipov to block a potentially disastrous decision.

Baby steps away from the abyss. Efforts to control AI-enabled weapons systems have stalled at the United Nations, where discussions of a “ban on killer robots” have resulted in lengthy definition debates and no real progress. Conventional conflicts between major militaries, moreover, would likely derail even the most unambitious efforts to direct new technologies. The devastation of such a conflict, along with the weakened international system, can be among the greatest risk factors. William MacAskill puts it simply in his latest book What we owe to the future: “When people are at war or fear war, they do stupid things.” (MacAskill is an advisor to Founders Pledge, my employer.)

It’s easy to feel fatalistic about these issues, but I’m optimistic that experts can do a lot in the short term. We’ve done it before. In the immediate aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis, a flurry of activity resulted in concrete risk mitigation measures, most notably the Nuclear Hotline, which enabled direct communication between executives in times of crisis. Later in the Cold War, Ronald Reagan and the late Mikhail Gorbachev worked together to reduce superpower inventories; Today there are about one-sixth as many nuclear weapons worldwide as there were in 1986. Thanks to their efforts, humanity is arguably in some respects safer today than it was 60 years ago.

Policymakers, philanthropists, and academics can draw on Cold War-era risk reduction as the next steps for global catastrophe risk. When it comes to AI governance, cold warriors’ favorite tools for confidence-building measures can build trust and reduce the risk of misunderstandings. For autonomous weapons, policymakers can emulate the success of the 1972 Maritime Incidents Convention and consider mechanisms such as an International Autonomous Incidents Convention to create a process for settling disputes related to AI-enabled systems. Regarding nuclear safety, policymakers can update Cold War risk mitigation measures, including projects to increase the resilience of crisis communication hotlines.

Existing hotlines and most communications systems seem most likely to fail precisely when they are most needed (e.g., when conditions deteriorate in the early stages of a major war). Research on increasing the resilience of such systems under extreme crisis conditions could therefore be particularly valuable if it enables explicit negotiation between executives and limits escalation. Finally, Cold War dialogues such as the Pugwash Conferences can facilitate unofficial discussions between the United States and China about new technologies, which can help ease tensions and avoid unwanted technology races.

At Founders Pledge, where I work, these emerging risks and the existence of controllable interventions is one reason why we have just launched a new Global Catastrophic Risks Fund focused on finding and funding effective solutions to these problems. Other efforts to reduce global disaster risk are also underway, including efforts to raise the profile of and manage these problems (see, for example, the Global Catastrophic Risk Management Act in Congress).

Sixty years ago mankind was lucky. Today we cannot afford to continue to rely on our luck.