How to understand what’s going on with UK mortgage rates

The UK mortgage market has tightened as confidence in the economy has faltered in recent weeks. Lenders withdrew more than 1,600 mortgage loans after Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng’s September mini-budget sent the UK economy into a tailspin. Interest rates on the remaining mortgage products have risen to record levels – the average two-year and five-year fixed rates have now exceeded 6 percent for the first time since 2008 and 2010 respectively.

The Bank of England has intervened to calm the situation. But that help currently has an end date of Friday October 14, after which it’s unclear what will happen in the financial markets affecting people’s mortgage rates. This is a key issue for many people: 65% of all residential properties are owner-occupied, and mortgage payments eat up around a sixth of household income on average.

A look at how the market has performed over time can help explain how we got here and where we are going — basically flipping headlong into a period of high interest rates, low credit approvals, and flat home prices.

All financial markets are driven by information, trust and liquidity. Investors absorb new information that inspires confidence or fuels uncertainty, and then they decide how to invest their money. When the economy falters, confidence dwindles and the interest rates banks have to pay to access finance in the financial markets – which affect mortgage rates for borrowers – become unpredictable.

Banks don’t like uncertainty, and they don’t like people defaulting on their loans. Rising interest rates and uncertainty increase their risk, reduce the volume of mortgage sales and squeeze their profits.

How banks think about risk

Once you understand this, it becomes much easier to predict how banks will behave in the mortgage market. Take, for example, the time before the 2008 global financial crisis. In the early 1990s, controls over mortgage lending were relaxed, so mortgage product innovation was a firm trend by the early 2000s. This has led to mortgages being offered for 125% of a property’s value, banks lending four times their annual salary (or more) to buy a home, and allowing self-employed borrowers to “self-certify” their income.

The risks at this point were low for two reasons. First, the liberalization of mortgage criteria brought more money into the market. This extra money chased the same supply of homes, raising house prices. In this environment, even when people defaulted, banks could easily resell repossessed homes, making default risks less of a concern. Second, at this time, banks began moving their mortgages to the financial markets, shifting the risk of default to investors. This freed up more money to lend as mortgages.

Read more: How bonds work and why everyone is talking about them right now: A financial expert explains

The Bank of England’s interest rate also fell during this period from a high of 7.5% in June 1998 to a low of 3.5% in July 2003. People wanted housing, mortgage products were diversified and house prices were rising – perfect conditions for a booming housing market. Until, of course, the global financial crisis broke out in 2008.

Authorities responded to the financial crisis by tightening mortgage rules and going back to basics. This meant increasing the banks’ capital – or protection – over the mortgages they had on their books and tightening the rules on mortgage products. Essentially: goodbye self-certification and 125% loans, hello to lower income multiples and bloated bank balance sheets.

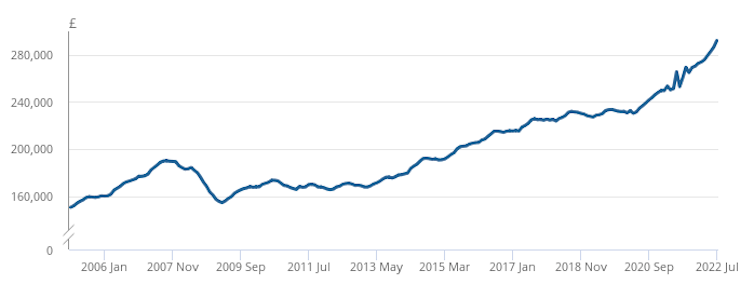

The result of these changes was that fewer people were able to qualify for a loan to buy a home, with average house prices in the UK falling from more than £188,000 in July 2007 to around £157,000 in January 2009. The damage was so deep they had only partially recovered Some of these losses reach £167,000 by January 2013.

Average house price in Great Britain, January 2005 to July 2022:

HM Land Registry, Registers of Scotland, Land and Property Services Northern Ireland, Office for National Statistics – UK House Price Index

New restrictions

Of course, prices have been booming again lately. This is partly because banks have slowly relaxed, albeit with less flexibility and more regulation than before the global financial crisis. This limitation in flexibility limited product choices, but low interest rates and low monthly payments have encouraged individuals to take on more debt and banks to lend more.

The availability of credit drives house prices, so the cycle begins again, albeit this time within a more regulated market. However, the outcome has been largely the same: average house prices have risen to just under £300,000 and the total value of gross mortgage loans in the UK has risen from £148bn in 2009 to £316bn in 2021.

But as new information hit the markets – starting with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine earlier this year – everything changed and confidence rose. The resulting supply-side constraints and rising fuel prices have fueled inflation. And the Bank of England’s very predictable response was to hike interest rates.

Why? Because rising interest rates are intended to discourage people from spending and encourage them to save instead, thereby relieving the burden on the economy. However, this increase in interest rates, and therefore monthly mortgage payments, comes at a time when rising fuel prices are already drastically reducing people’s disposable income.

Garage Stock / Shutter Stock

Mortgage Market Outlook

So what about the mortgage markets going forward? The current economic situation, while radically different from that of the 2008 financial crisis, is driven by the same factor: confidence. The political and economic environment – the policies of the Truss administration, Brexit, the war in Ukraine, rising fuel costs and inflation – has eroded investor confidence and increased risk for banks.

In this environment, banks will continue to protect themselves by streamlining their product range while increasing mortgage rates, the size of deposits (or LTVs) and the management fees they charge. Loan approval is already declining and cheap mortgages are quickly disappearing.

Demand for home loans will also continue to fall as potential borrowers are faced with a reduced product range and increasing borrowing costs and monthly payments. Few people make big financial decisions when uncertainty is so high and trust in government so low. On an optimistic note, the current situation will see UK house prices plateau, but given the continued uncertainty stemming from government policies, it is realistic to expect downturns in certain areas as financial market volatility persists.