What India’s latest farm exports data show

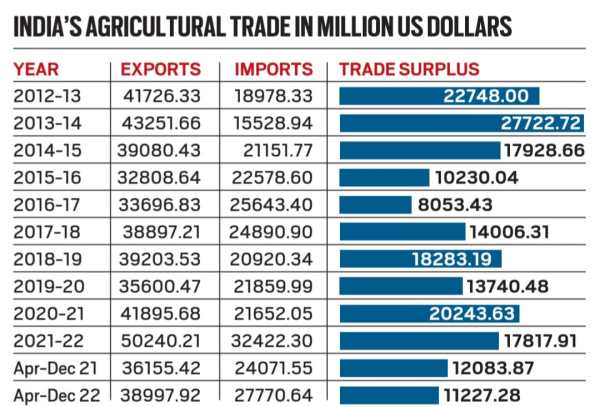

India’s agricultural exports are poised to hit a new high in the fiscal year ending March 31, 2023. But also the imports, which reduce the overall agricultural trade surplus.

Government data shows that the value of agricultural exports from April to December 2022 was US$39 billion, up 7.9% from US$36.2 billion in the corresponding period last year. At the current rate, it is expected to surpass the record $50.2 billion in exports achieved in 2021-22.

Equally significant, however, are imports of agricultural products, which reached USD 27.8 billion in April-Dec. 2022 up 15.4% from $24.1 billion in April-Dec Agricultural Trade Account. The attached table shows that even in 2020-21 ($20.2bn) and 2021-22 ($17.8bn) the surpluses were lower than the $22.7bn and $27.7bn respectively .USD from 2012-13 and 2013-14 respectively.

India’s agricultural trade in million US dollars.

India’s agricultural trade in million US dollars.

The drivers of the export…

The two big contributors to Indian agricultural export growth were rice and sugar.

India shipped an all-time high of 21.21 million tonnes (mt) of rice worth US$9.66 billion in 2021-22. This included 17.26 tons of non-basmati rice (worth $6.12 billion) and 3.95 tons ($3.54 billion) of basmati rice. In the current fiscal year, the growth was mainly led by basmati rice. Its exports have increased by 40.3% in value (from $2.38 billion in April-December 2021 to $3.34 billion in April-December 2022) and by 16.6% in volume (2.74 t on 3, 20 t) increased. The corresponding increases were smaller for non-Basmati exports: 3.3% in value ($4.51 billion to $4.66 billion) and 4.6% in volume (12.60 t to 13.17 t).

Sugar is perhaps more spectacular. Sugar exports hit a record $4.60 billion in 2021-22, up from $2.79 billion, $1.97 billion, $1.36 billion and $810.90 million in respectively the previous four financial years. This fiscal year saw another 43.6% increase, from $2.78 billion in April-December 2021 to $3.99 billion in April-December 2022.

Indian exports of rice and sugar are on track to reach, if not surpass, US$11 billion and US$6 billion respectively in 2022-23. Seafood exports are also expected to top last year’s peak of $7.77 billion after posting a marginal 2.7% jump to $6.29 billion from $6.12 billion in April-December 2021 -dollars in April-December 2022.

However, exports of some high-profile items have stalled or slowed. The value of buffalo meat shipments fell 5.1% from $2.51 billion in April-December 2021 to $2.39 billion in April-December 2022. Spices were also down 6.7% $2.95 billion to $2.75 billion. While wheat exports are up 3.9% from US$1.45 billion to US$1.51 billion, they are expected to exceed the fiscal year 2021-22 level of US$7.23 million ( USD 2.12 billion) will not hold or even reach in May 2022.

…And that of imports

More than an overall slowdown in exports, growth in imports should be a concern. This is mainly due to three raw materials.

First are vegetable oils, whose imports increased from $11.09 billion in 2020-21 to $18.99 billion in 2021-22 and even more in the first nine months of 2022-23 in the same period of the last fiscal year – from $14.04 billion to $16.10 billion, or 14.7%. According to Solvent Extractors’ Association of India, India’s total edible oil imports increased from 13.13 million tons in 2020-21 to 14.03 million tons in oil year 2021-22 (November to October), further increasing by 30.9% from 2.36 million tons in November-December 2021 to 3.08 million tons in November-December 2022. Imports now account for over 60% of the country’s estimated annual oil consumption of 22.5-23 million tons.

The second is cotton. India’s cotton exports reached an all-time high of $4.33 billion in 2011/12. It stayed at relatively high levels ($3.64 billion) through 2013-14, before plummeting to $1.62 billion in 2016-17 and $1.06 billion in 2019-20. Thereafter, there was a rebound to $1.90 billion in 2020-21 and $2.82 billion in 2021-22.

But during this fiscal year, not only have exports plummeted to $512.04 million from April to December (from $1.97 billion in April to December 2021), imports have also fallen from $414.59 million in the same period US dollars increased to 1.32 billion US dollars. In other words, India has gone from being a net exporter to a net importer of cotton.

The third commodity is cashew. From April to December 2022, imports recorded a 64.6% increase to US$1.64 billion from US$996.49 million in April to December 2021, although exports of cashew products increased by 344, 61 million US dollars collapsed to 259.71 million US dollars. A similar trend was observed for spices, with exports falling (from $2.95 billion to $2.75 billion) and imports increasing slightly ($955.75 million to $1.03 billion).

The political implications

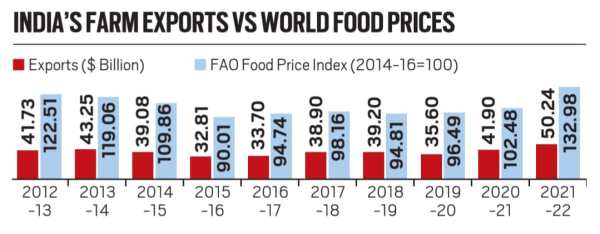

The chart shows how closely linked India’s agricultural performance is to international commodity prices.

India’s agricultural exports compared to world food prices.

India’s agricultural exports compared to world food prices.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) food price index – with a base value of 100 for 2014-16 – averaged 122.5 points in 2012-13 and 119.1 points in 2013-14. Those were the years when India’s agricultural exports were $42-43 billion. When the index plummeted to 90-95 points in 2015-16 and 2016-17, exports also fell to $33-34 billion. The recovery in exports in 2020-21 and 2021-22 happened together with – rather backwards – rising global prices and the FAO index, which averaged 102.5 points and 133 points in the two years.

The FAO index peaked at 159.7 points in March 2022, shortly after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. It has fallen every month since, with the latest reading of 131.2 points for January 2023 being the lowest after September 2021’s 129.2 points.

Based on past correlation, it is reasonable to assume that this will cause India’s agricultural exports to slow in the coming months. Furthermore, this could be accompanied by increased imports, as was the case from 2014-15 to 2017-18. In this case, the focus of policymakers may also need to shift from a pro-consumer (to the point of banning/restricting exports) to a pro-producer stance (tariff protection against unbridled imports).

Second, the government must do something about cotton and cooking oils. India’s cotton production has fallen from a peak of 398 lakh bales in 2013-14 to a 12-year low of 307.05 lakh bales in 2021-22. The impact of the non-approval of new genetic modification (GM) technologies following first-generation Bt cotton is clearly evident and is affecting exports as well. A proactive approach is also needed on edible oils, where the cultivation of hybrid GM mustard has been allowed with great reluctance – and which is now a matter before the Supreme Court.