NASA scientists study how to remove planetary ‘photobombers’

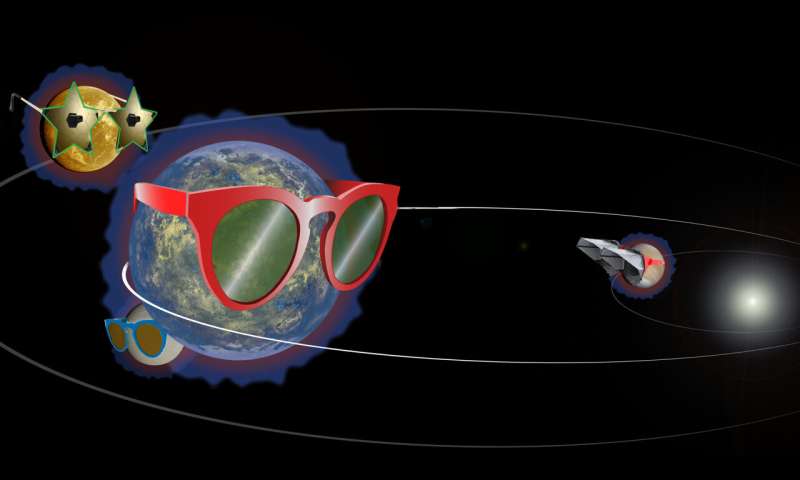

A cartoon illustrating the planetary photobombing concept. Photobombers like Mars and the Moon could sneak into an image of Earth if you tried to observe them in much the same way scientists try to find and understand potentially habitable worlds outside of our solar system. Credit: NASA/Jay Friedlander/Prabal Saxena

Imagine you are going to an amusement park with your family and ask a park employee to take a group photo. A celebrity walks by in the background and waves at the camera to steal the focus of the photo. Surprisingly, this concept of “photobombing” is also relevant for astronomers looking for habitable planets.

When scientists point a telescope at an exoplanet, the light the telescope receives could effectively be “contaminated” by light from other planets in the same star system, according to a new NASA study. The research, published in The Letters of the Astrophysical Journal on Aug. 11 modeled how this “photobombing” effect would affect an advanced space telescope designed to observe potentially habitable exoplanets and suggested possible ways to overcome this challenge.

“If you look at the Earth next to Mars or Venus from a distant vantage point, you might think they’re both the same object, depending on when you observed them,” explains Dr. Prabal Saxena, a scientist at NASA Flight Center’s Goddard Space in Greenbelt, Maryland, who led the research.

Saxena uses our own solar system as an analogue to explain this photobombing effect.

“For example, depending on observation, an exo-earth could be hiding inside [light from] We mistakenly believe it is a large Exo-Venus,” said Dr. Saxena. Venus, Earth’s neighbor, is generally considered hostile to habitability because surface temperatures are so high that lead could melt – so this mixing could mean scientists miss Venus as a potential habitable planet.

Astronomers use telescopes to analyze light from distant worlds to gather information that might show if they could support life. A light-year, the distance light travels in a year, is nearly six trillion miles (over nine trillion kilometers), and there are about 30 sun-like stars within about 30 light-years of our solar system.

Artist’s concept of Kepler-186f, an Earth-sized exoplanet orbiting a red dwarf star in the constellation Cygnus. Credit: NASA/Tim Pyle

This photobombing phenomenon, in which observations of a planet are contaminated by light from other planets in a system, originates from the target planet’s “point spread function” (PSF). The PSF is an image formed by diffraction of light (the bending or spreading of light waves around an aperture) coming from a source and is larger than the source for something very distant (e.g. an exoplanet). The size of an object’s PSF depends on the size of the telescope’s aperture (the light-collecting region) and the wavelength at which the observation is made. For worlds around a distant star, a PSF can resolve in such a way that two nearby planets or a planet and a moon appear to merge into one.

If this is the case, the data scientists can gather about such an Earth analog would be skewed or influenced by the world or worlds that photobombed the planet in question, which could make detection and confirmation of an Exo-Earth difficult or impossible . a possible planet like Earth beyond our solar system.

Saxena studied an analogous scenario in which otherworldly astronomers could gaze at Earth from more than 30 light-years away, using a telescope similar to the one recommended in the 2020 Astrophysics Decadal Survey. “We found that such a telescope would sometimes see potential exo-Earths more than 30 light-years away, interspersed with additional planets in their systems, including those outside the habitable zone, for a number of different ones wavelengths of interest,” Saxena said.

The habitable zone is the region of space around a star where the amount of starlight would allow liquid water on a planet’s surface, which could allow life to exist.

There are several strategies to deal with the photobombing problem. This includes developing new methods of processing data collected from telescopes to mitigate the potential for photobombing to skew the results of a study. Another method would be to study systems over time to avoid the possibility of tight-orbiting planets popping up in each other’s PSFs. Saxena’s study also discusses how using observations from multiple telescopes or enlarging the telescope might reduce the photobombing effect at similar distances.

To look for extraterrestrial life, astronomers look for clues in the atmospheres of distant planets

Prabal Saxena, Photobombing Earth 2.0: Diffraction Limit Contamination and Uncertainty in Spectra of Habitable Planets, The Letters of the Astrophysical Journal (2022). DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/ac7b93

Provided by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

Citation: NASA Scientists Study How to Remove Planetary “Photobombers” (2022 August 17) Retrieved August 17, 2022 from https://phys.org/news/2022-08-nasa-scientists-planetary-photobombers. html

This document is protected by copyright. Except for fair trade for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is for informational purposes only.