Enthusiasts puzzle over how to save Oregon’s museum of gaming

Avid gamer Bryan Fosmire is sitting at his dining table in September 2022. He was forced to return to playing board games at home after Oregon’s Interactive Museum of Gaming and Puzzlery closed in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Kristian Foden-Vencil / OPB

Bryan Fosmire used to be a regular at the Interactive Museum of Gaming and Puzzlery in Oregon. Today, the 28-year-old mechanical engineer plays games like Terraforming Mars at his dining table in Dundee. But the museum gave him another, richer place to indulge his love of gaming.

“The first thing you’ll probably notice is the huge wall in the back full of shelves of games,” he said.

When it opened between 2010 and 2020, the Washington County Museum had a collection of about 9,000 games. His mission was to educate people and make the games accessible.

“They actually had exhibits in the room too. Even going back to ancient games, like where the first dice came from and how they used bones before that,” Fosmire said.

Shelves of games from the Interactive Museum of Gaming and Puzzlery before its closure in 2020.

Kyle Engen

The museum included a small shop and a small cafe. For Fosmire, it was a place to meet like-minded people.

“You would go in, and if there were people there, you could meet them and see if they wanted to play something,” he said. “If not, you could just bring your own group, grab something off the shelf and just play it.”

But the museum was forced to close as part of the nationwide pandemic shutdown.

“We have exactly the material that can transmit an infection,” said co-founder Kyle Engen. “Handling games and passing around dice and passing around pieces. So we had to close.”

Now the museum’s collection sits in boxes, packed in several lockers and homes throughout Washington County.

Museum co-founder Kyle Engen’s Washington County home is packed with games from the collection. He is looking for a new leadership and a new location for the museum.

Kristian Foden-Vencil / OPB

Engen and co-founder Carol Mathewson want to bring the museum back. But they have problems.

“I approached three or four universities around here, the anthropology departments,” Engen said. “I called, I emailed. No answer at all.”

The couple opened the original Museum of Gaming in Beaverton in 2010 after Engen couldn’t find work and they decided to try to make a living doing something they love.

He had been collecting games all his life. He spent his childhood playing fantasy games in Eugene with the likes of Richard Garfield, creator of the popular card game Magic: The Gathering.

For a few years, the museum made enough to keep its doors open, though it had to move a few times because landlords asked for higher rents.

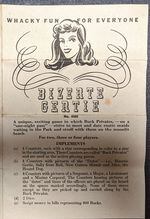

Museum co-founder Carol Mathewson is showing a copy of Bizerte Gertie, a 1943 game that doesn’t involve dating Alice the Hound Dog.

Kristian Foden-Vencil / OPB

But now Engen and Mathewson’s home is packed with boxes of old games: 50 versions of Monopoly, puzzles, mahjong, bingo, and rare games – like Bizerte Gertie from 1943.

“Anthropologically, games have everything to do with how we learn,” Mathewson said.

Bizerte Gertie, for example, was created for World War II soldiers. The goal was to go to a club, meet a beautiful woman and take her for a walk on the beach. There’s a flirtatious damsel on the box and three grinning military men. But in keeping with the times, the goal of the game was to avoid ending what the game manual calls “Alice the Hound Dog.”

One of the goals of Milton Bradley’s 1943 game Bizerte Gertie was that players should not end up with Alice the Hound Dog.

Kristian Foden-Vencil / OPB

Engen and Mathewson have spent years collecting such games from thrift stores, often spending 75 cents here or a few dollars there. They believe that games illustrate the eras in which they were created, like a 1969 game developed by Psychology Today magazine.

“It was called Blacks & Whites, and you couldn’t win the game as a black character. Period. That was the point of the game,” Mathewson said. “These things are metaphors that accompany us through all eras of history.”

Engen said her collection speaks to that story. Take playing cards for example. It’s not clear how they were invented, but one theory is that they began as promissory notes traded by Chinese soldiers in the seventh century.

“Because they were so far from the central government, they couldn’t pay the army. So they wrote scripts that said, ‘We owe you $10.’ on slips of paper. Then men started playing with it, and playing cards were invented,” Engen said.

Mathewson said that kind of story and context doesn’t get passed around in a store. Games need their own museum for this.

“What we want is a place where all of this really groovy stuff that we’ve learned through the research can be conveyed,” Mathewson said.

But after a decade of trying to keep the museum running and a pandemic, they’re tired.

“I’m no longer willing to do anything to keep it going 60 hours a week,” Engen said. “I’m fed up with this now.”

Kyle Engen and Carol Mathewson’s home is packed with games from the collection.

Kristian Foden-Vencil / OPB

In addition to a new management, the museum also needs a new location. The organizers have tried to seek help from local businesses and government agencies. They keep getting asked to just open a store where people can buy new games and see the collection at the same time. But there are already plenty of gaming stores and cafes in the Portland area, and even at least one gaming restaurant, the Mox Boarding House.

Mike Williams, manager of economic development for the city of Beaverton, said city guides might be able to help – but first they need information.

“How much space do you need? What can they afford? How do you intend to use the space?” he said. “And after we know these things. We can help you find a location. In this case, we also thought, ‘Hey, a bit of specialized technical support would also be helpful.’”

Mathewson said they have a lot of people interested in starting a museum, but they need a benefactor. “We need someone with nice deep pockets, because that’s what the symphony or the art museum has,” she said.

There was hope that some of Engen’s old games could provide the money for a reopening. Collector cards can be worth $100,000 or more. But over the years, some of the collection’s most prized cards have disappeared as people played with them and cataloged the collection.

Interactive Museum of Gaming and Puzzlery before its closure in 2020.

Kyle Engen