‘Honey-child, listen to me’: a radical Buddhist nun on how to be happy in a crazy world | Buddhism

IIt’s a Tuesday evening in the small country town of Milton on the NSW south coast, and the smell of freshly brewed chai and homemade soup about to be served wafts through the drafts in the Country Women’s Association hall as the discussion switches between death , killing, war, abortion, prison and suffering.

About 50 people, some longtime members of the local Buddhist group, other curious newcomers, sit cross-legged on the wooden floor or on plastic chairs, a portrait of a young Queen Elizabeth II looks down and listens to a Buddhist nun. The topic of the evening: “How to stay positive in a negative environment.”

“Our problem is that we think the outside world is the main cause of our suffering – and our happiness,” says Venerable Robina Courtin, an Australian, now 77, who was ordained in the Gelugpa Tibetan Buddhist tradition in the late 1970s.

“We understand that when it comes to being a musician, you program yourself and stuff like that she are the main reason to become a musician – the work is in your head, you need precision and clarity and perfect theory and then you practice and practice. We know we create ourselves in that sense,” she says.

“But when it comes to turning ourselves into a happy person, we don’t think we have that ability. But the Buddhist approach is that we create ourselves, be it a musician or a happy person. We are the boss.”

But what about all the added suffering of recent years, asks a woman, citing Covid, floods and war in Ukraine. Courtin tells the story of two imprisoned Tibetan women who were tortured and sexually abused but were still able to “interpret the experience” in a way that they “could endure”.

The questioning woman looks dissatisfied. “What is it?” asks Courtin. “Come on, say it, it’s important.” Courtin can be warm and piercingly direct at the same time — when a questioner at the event the night before stopped her sentence mid-sentence, she replied, “Can’t you hear I’m trying to get yours.” answer the question!” – and it takes a moment for the woman to reveal what she thinks. “It just doesn’t seem practical,” she finally says.

“It comes in handy when you’re being sexually abused in prison,” says Courtin. “We have the power to change the way we interpret our lives and they have been able to do that. And they could even feel sorry for their torturers. The result of that? You haven’t lost your mind. It’s not moralistic; it’s really convenient.”

“Darling, listen to me,” Courtin says more gently. “Our problem is that we can’t deal with our own suffering or the suffering out there, so we just want to make it all go away. We can not. All we can do is do our best in this insane asylum called Planet Earth.”

From convent school to death row

Earlier that day, over lunch, Courtin explained: “I’ve always been involved in the world. I like the world and I like crazy people.” She is a “newspaper and news junkie”; Her favorite publications include the Financial Times, The Economist and the Washington Post.

Courtin grew up in Melbourne, one of seven children, in a wild, poor, Catholic household. As the “naughtiest child in the family”, she was taken to a convent school at the age of 12. “I was in heaven, it was bliss,” she says. Not only did she finally have her own bed, but “there was no chaos around me, I had discipline. I went to mass every day. I was in love with God and Our Lady and the Saints. It was perfect for me.”

In her late teens she discovered boys. Realizing that she “couldn’t have God and boys at the same time,” she “deliberately” chose “Goodbye God, hello boys.” A used record bought for sixpence led her to jazz. “I have this 7” LP that says ‘Billie Holiday’ on it. I had no idea, I wondered who he was! That opened me up. It just blew my mind because it opened me up to this Black American experience with people who are suffering.”

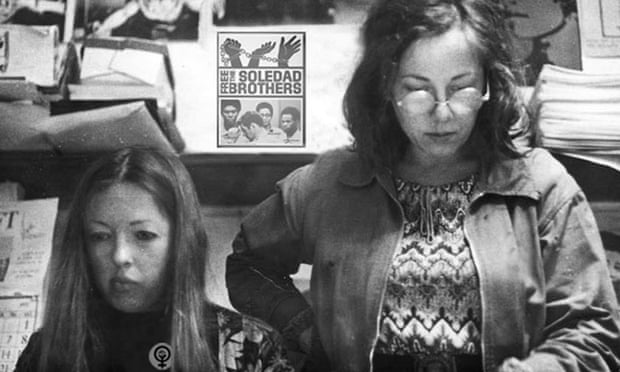

In the late 1960s, Courtin made his way to London “rough and ready for revolution”. There she joined “radical left” demonstrations and supported the Black Panther movement. In 1971 she began working full-time for Friends of Soledad, a British political activist group supporting three black American prisoners accused of murdering a white prison guard. Then she switched to the radical feminist movement. She shed her love for men, became a “radical lesbian feminist,” learned martial arts, and moved to a lesbian-run dojo in New York City.

In 1976, back in Australia, in Queensland, 31-year-old Courtin, with a broken foot that stopped her martial arts practice, saw a poster advertising a lecture by two Tibetan Buddhists – Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche – and decided to join. “I found my way there,” she says. “I’ve always been looking for a way to see the world, why is there suffering, what are the causes of it? And I think I had exhausted all possibilities as to who is responsible for the suffering of the world.”

Since her ordination 44 years ago, Courtin has worked as an editor of Buddhist magazines and books. In 1996, after receiving a letter from a young Mexican-American ex-gangster who was serving three life sentences in a maximum-security prison in California, she founded the Liberation Prison Project, a nonprofit organization that provides Buddhist teachings and support for inmates.

Courtin ran the program for 14 years, helping thousands of inmates and still keeping in touch with her “prison friends”. She recently visited one who has been on death row in Kentucky since 1983. “He lives in this prison dump, no sensual pleasures whatsoever, the food is just awful, no freedom at all, much to do, he’s considered a monster and he’s such a happy guy,” she says. As a practicing Buddhist, “he is fulfilled and content. He’s worked on his wits, taking responsibility for his actions and while he would love to be released from prison, he accepts his reality. ‘I’m ready for that electric shock,’ he told me.”

I ask Courtin if she’s angry about this man’s plight. “No, I will not do that. I try to help him where he is. It is,” she says. “I remember when I was a radical political activist in London in the early 1970s when I was angry. That’s when I was angry. Racism, sexism, injustice are just as bad now, if not worse – the prison system in America is fucking outrageous – but I work differently now.

“The problem is that we confuse seeing a bad thing with anger. We feel like we’re throwing the baby out with the bathwater if we give up anger.” Courtin says she’s “still an activist” but maintaining anger is like stabbing yourself with a knife—”it only paralyzes you”. Instead, she practices what she calls bold compassion. “There is a saying in Buddhism, A bird needs two wings, wisdom and compassion. Wisdom is the inside, composed. Compassion is putting your money where your mouth is and helping the world.”

Live in this world without losing your mind

Since the late 2000s, Courtin has been living out of a suitcase, teaching at Buddhist centers around the world, and only ground to a halt in Sante Fe in March 2020 when the pandemic hit. She started teaching via Zoom — “I adore Zoom” — and a friend set up and runs her social media. Her TikTok account, which has 85,600 followers, has short videos, sometimes responding to current events, with titles like “How to Live in This World Without Losing Your Mind.”

“There is a way to use the world to develop your practice,” she says. Take former US President Donald Trump, for example. “I would watch Mr. Trump and instead of ranting and ranting about how bad he is, I would say, ‘Well, those are lies, I acknowledge that. That’s anger, I acknowledge that. That’s vanity, I acknowledge that. That’s arrogance, I acknowledge that. There’s not a single damn delusion Mr. Trump has that I don’t have. The Buddhist view is that we all have these states of mind; We’re all sitting in the same boat. So I say, ‘Thank you for showing me how not to be.’”

Courtin recently shared on social media that her sister Jan had died after an accident at home. She says the huge response to her post “touched me deeply because people were so nice.” She boarded a flight from the US as soon as she found out about the accident. In a Melbourne hospital room with her siblings when Jan was taken off life support, Courtin whispered the Buddhist mantras that accompany death while the rest of the family happily sang the Sydney Swans team song.

Once Courtin wraps up this current Australia teaching tour, she will move to New York City where she plans to settle “for the last few years of my life”. She plans to write and edit, continue her personal study and Buddhist practice, and teach via Zoom. Maybe “I go to a jazz club at night,” she says, before adding, “Just kidding, I probably won’t go to the jazz club.”

“I’ll try not to waste my life. Try to stay useful. Be useful before I drop dead.”