How to Create Climate Laws that Stick

The framework created by the UK with the 2008 Climate Change Act has been widely replicated around the world.

Article content

(Bloomberg) —

Advertisement 2

content of the article

The UK, like many countries across Europe, is preparing for a painful winter. To save households from unaffordable energy, newly appointed Prime Minister Liz Truss has agreed to limit and pay for the bills by raising the national debt. At the same time, she is calling for a review of the country’s net-zero targets and her energy minister wants to drill for every drop of oil and gas.

content of the article

That may seem like an existential threat to the UK’s climate ambitions, but the country is unlikely to back down on any of its goals, said Bryony Worthington, a member of the House of Lords. It might even make them stronger, she added, because “the solutions to climate change, the solutions to air quality and the solutions to high energy prices are all the same,” Worthington said. “You use less energy and you use cleaner energy.”

advertising 3

content of the article

Worthington is not only a keen observer of the climate-energy landscape in the UK and globally – she was one of the authors of the Climate Change Act of 2008. The historic law committed the country to net-zero emissions by 2050. The framework it creates also ensures that the government stays on course even in the face of multiple crises.

Worthington was the first guest on Bloomberg Green’s new podcast, Zero, hosted by me. We talked about how the law came about, why almost all politicians voted for it, and how it’s structured to be flexible, but not overly so. I hope you listen to the full conversation wherever there are podcasts, and here are the links for Apple, Spotify, Google, and Stitcher.

advertising 4

content of the article

Worthington’s finding is relevant beyond the UK – the Climate Change Act offers an approach that nations like New Zealand, France and Sweden have already copied. To understand why the framework is so powerful, it is necessary to examine three key elements of it: carbon budgets, empowerment powers, and an independent watchdog.

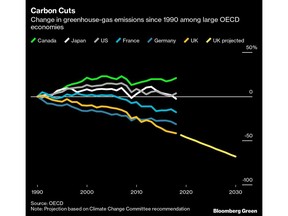

First, the UK is locked into five-year carbon budgets that are becoming increasingly stringent, taking the country to net-zero emissions by 2050. So far the UK has met its first two budgets and is on track to meet the third by the end of this year. “Ambition and flexibility go together,” Worthington said, which is why the government is working in five-year windows rather than one-year budgets.

advertising 5

content of the article

However, the UK is starting to get off course in meeting future budgets. When environmental groups sued the government earlier this year over what they saw as inadequate climate policies, the binding nature of the 2050 target helped them win in court: the judge asked the government to spell out exactly how it will ensure that action is taken to achieve the there are climate targets.

Second, the law gives the government the power to issue policies that can help it meet climate targets. These powers are likely to be used to introduce, for example, a zero-emission vehicles mandate that will increase sales of non-combustion vehicles until fossil fuel vehicles are no longer sold in the UK. The government can also use the law to redirect subsidies, for example for agriculture, to reducing emissions from land use.

advertising 6

content of the article

Eventually, the law created the Committee on Climate Change. The panel is funded by the UK Government but offers an independent analysis of whether the government is on track to meet climate targets and what kind of action will help. As the energy world changes and clean technologies become cheaper (or not), the committee can update the government on how to most effectively meet its economic, energy and climate goals.

That is the strength of the law itself, but its impact has been reinforced by a significant increase in public support. When the law was passed in 2008, members of all political parties felt compelled to address public concerns about climate change. Around 463 MPs voted in favor of the law, only three against.

Since then, public concern has only increased, which is another reason why, according to Worthington, trying to roll back climate targets “is not going to be high on anyone’s agenda”. This summer alone, Britain experienced an extreme drought and a record-breaking heatwave.

Akshat Rathi writes the Zero newsletter, which examines the global race to reduce emissions through the lens of business, science and technology. You can email him feedback.