How to cycle to Iceland, part one: pedalling through Denmark | Denmark holidays

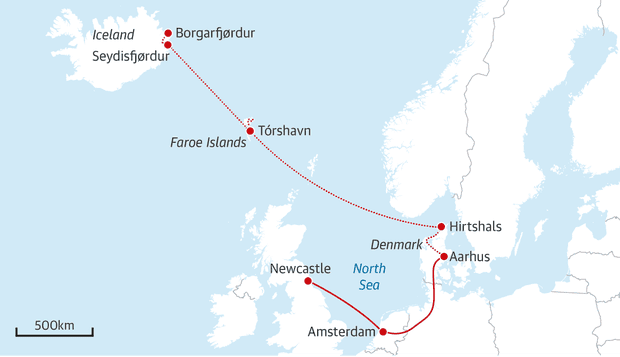

A everything is ready a week before departure: the polished bicycle loaded with four carefully packed panniers, ferry and train journeys booked, accommodation and campsites reserved. Cycling to Iceland is a complex affair: ferries to Amsterdam from Newcastle, trains to Aarhus, bike up through Jutland to the port of Hirtshals near the northern tip of Denmark, ferries on to the Faroe Islands, which I’ll explore by bike before heading to further bike tours through the east of Iceland. A total of three weeks and no flights required. A small sacrifice for the climate emergency, but also a chance to make everyone aware of the wonderful adventures that can be had without flying.

But four days before leaving, I find myself in the hospital staring at a very sick person who cannot be left behind. Weeks of planning and preparation are at stake. The day of departure passes, but then the miracle of intravenous antibiotics happens and I realize I can still travel and catch up on my own itinerary if I make a few changes.

I have to give up the idea of taking my own bike and using rented machines instead; I also have to leave immediately and – gulp – take a short flight. I quickly stuff a few things into two panniers and only fly hand luggage to Denmark. From the airport I take trains and buses to the Jutland town of Thisted, where I rent a Dutch bike with pedal brakes. I load the panniers and my handlebar bag, then set off into the hilly, empty countryside towards the coast and some dark clouds.

It feels good to be on the go. Planning an international trip without flying by bike is a lot harder than it should be. Ferry services have been cut back in recent years – the journey would be much easier if there were still a ferry between the UK and Scandinavia. Additionally, taking bikes on international trains can be frustratingly difficult (regional connections are much easier). Our transportation systems are hopeless when it comes to doing something good for the planet.

As I finally near the Jutland coast, I run headlong into a vicious north-west gale bringing frigid volleys of rain straight from the North Sea. Any optimism is quickly flushed out of me. I arrive at Hanstholm campsite (two-bed cabins from £63 a night) at dusk, soaked, shivering and bike-hating. All camping gear is back home. I’ll take a small chalet. I unpack. I pull out a down jacket and gloves. How did they get in there? Stupid things to pack in a heat wave, but I’ll put them on gratefully. I brought the wrong bag. But what is that? A copy of War and Peace, the book I had read and wanted to leave behind. I open any page and start reading.

Tolstoy’s masterpiece is probably the most poignant read I could have chosen: the tale of how everyone takes part in a senseless rush towards predictable doom. Even my tiny no-fly post has already failed.

When I wake up the next morning it doesn’t look so gloomy. The sun shines in the blue sky as I pedal across grass towards a raging sea. Denmark’s West Coast Cycle Route is 450 miles long and consists of dunes, forests and back roads, but this morning all I want is beach.

Without consulting the map – the one I left in Britain – I continue into the sand and turn north. By staying on the edge of the waves, I can make decent progress unless I try to tack, causing me to fall off. A cloud of curlews rises to my right, the wind holding the birds so close I feel like I can reach out and pet their long curved beaks. The sea thunders in my ears and I don’t think about anything anymore. I love cycling. i love denmark

As the tide finally pushes me onto the softer sand, I’m forced inland to the grassy dunes where I find a marked trail. A chain of black diamonds thrown onto the path suddenly uncoils and glides away into beds of wild snapdragons and orchids. This is adder territory. At Thorup Strand I find a fishing collective selling excellent fish and chips. Late in the afternoon I’m at Svinkløv campsite (tent for two for £47) where my permanent tent has a very comfortable bed. I love Denmark’s reserved, sane mentality. There’s no fuss, no mess, and certainly no hype.

As King Frederick VI. early 19thth In the late 19th century he proclaimed it the finest part of his empire (which then included Norway, Greenland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, a trio of Caribbean islands, the Nicobar Islands and the Bengali city of Frederiknagore, now Serampore).

There is nothing flashy or spectacular, just a few neat lawns, a thatched windmill and a long beach. There are simple sleeping huts along this coastal path, which is where I originally intended to camp, but now I’m passing. In the town of Blokhus, over lunch in the thatched-roof restaurant Futten, I strike up a conversation with an 82-year-old doctor, whose practice was once in Greenland, and his son. “I liked to make house calls,” he remembers, “I went dog sledding.” In the summer he came back here, to the family’s summer cottage. I envision a weatherproof hut filled with pieces of driftwood and the skulls of sea creatures. Suddenly I feel a connection to my onward journey, the vast northern seas salted with rugged volcanic eruptions and ice caps. For the first time I feel the benefits of arriving slowly over land and sea. There is time to talk and build knowledge and expectations.

The doctor’s son speaks about the egalitarian nature of the Danes. “When a group of 9th-century Viking warriors were asked who their leader was, they replied, ‘We are all leaders’.”

He asks if I like the flat landscape. “For us Danes, the wilderness is not mountains, but sea.”

I continue up the beach, following the undulating spray line to Løkken and what turns out to be a first class B&B, Villa Vendel (doubles from £104) in a lovely old fashioned house with a bike shop in the former stables. From here, in the pouring rain again, I push the bike over a headland and into the spectacular remains of WWII German gun emplacements. The sea pulls her down and slowly drowns her. Before long their dark corridors will be fish nurseries.

Aside from the occasional deep inland loop, I’m almost always in the sound of the sea on this trip and whenever I can I cruise on the beach. Cars are allowed in places and the sand is kicked up, but I always find a firm footing on the water. Sometimes I carry the bike into the dunes and lie down out of the wind, watch birds and flowers, and then go for a swim. To dry myself, I face the wind. No towel. I buy sandwiches and coffee in nicely painted clapboard cafes.

I reach Hirtshals Port the night before the weekly ferry to the Faroe Islands departs and check in at the Montra Hotel (doubles from £90) near the quay. The town itself is a strapping, seaworthy place where you could buy a fishing rod and knife, as well as pants, socks, bottled water and towels. But not me. No place. My son Conor, who lives in Berlin, comes by train to accompany me and in the morning, in the sunshine, we make our way to the towering Smyril Line ship Norröna, which has surfaced. We will rent bikes when we get to Tórshavn, but that’s all I know: cycling is supposed to be new in the Faroe Islands. On the quay, I chat with a Faroese crew member: “I own a bicycle,” he tells me. “But I’ve never ridden it. There is no cycling in the Faroe Islands. It’s too cold, too windy and we have a lot of long, dark tunnels.”

We board the ferry with some excitement, spiced with a little trepidation. After the gentle charms of Jutland, the epic bike ride seems to get much tougher.

The trip was made available by Visit Denmark. Bike Havs in Løkken hire bikes from £13.50 per day (e-bikes from £22), with Collections and returns throughout Jutland. DFDS ferries run daily from Newcastle to Amsterdam. A Eurail “four days a month” pass costs approx £200. Smyril Line runs weekly in autumn from Hirtshals to Tórshavn in the Faroe Islands, passenger with bike from £80 in one direction