How to read a hurricane map

Hurricanes Fiona and Ian have claimed the lives of an unconfirmed number of people, caused hundreds of millions of dollars in damage and left millions without power. For all of these reasons, weather agencies spend a great deal of time and resources trying to predict the possible paths hurricanes might take — but how they convey those forecasts to the public can still cause confusion.

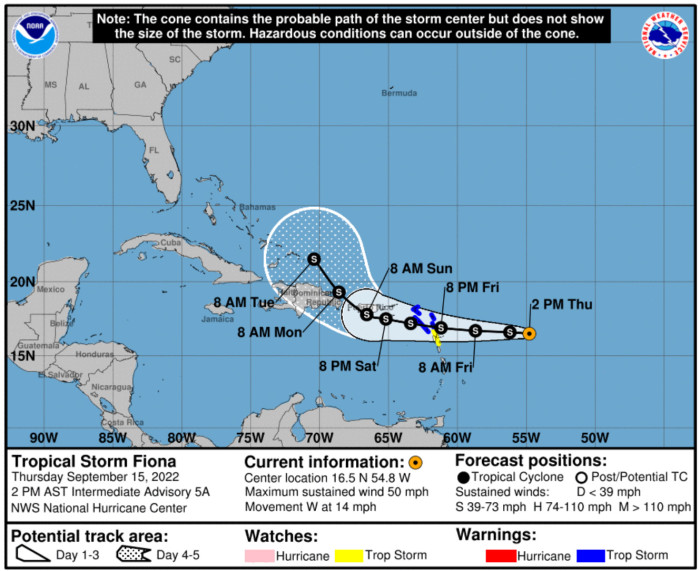

The most common way of showing a hurricane’s predicted path is used by the National Hurricane Center (NHC). It is referred to as the “Cone of Uncertainty”.

This graphic is very susceptible to misinterpretation or even outright manipulation if you don’t fully understand what it shows.

“Sharpiegate” was the most recent infamous example, when former US President Donald Trump presented a card with a hand-drawn bow added to the cone.

“Sharpiegate” refers to an incident in 2019 when Donald Trump presented a forecast map altered with a black marker to show Alabama on the path of Hurricane Dorian © Tom Brenner/Bloomberg

Two of the most common misconceptions with the map are that it a) shows the size of the hurricane as it develops, or b) that living outside the cone will keep you safe.

None of these are true, and that’s why there’s a big clue at the top of the map.

What the uncertainty cone actually represents is “that probably [emphasis added] Track of the center of a tropical cyclone and is formed by enclosing the swept area by a series of circles (not shown) along the forecast track (at 12, 24, 36 hours, etc.),” advises the NHC.

“Each circle is sized so that two-thirds of the historical official forecast errors over a 5-year sample fall within the circle,” notes the NHC.

This means there is a one in three chance of the hurricane path falling outside the cone. High winds, torrential rains and storm surges could wreak havoc on these areas that people may have thought safe.

Alberto Cairo, Knight Chair in Visual Journalism at the University of Miami School of Communication and author of numerous books on data visualization such as How charts lieexplains how easily hurricane maps can be misinterpreted.

“The cone graphic is deceptively simple. That becomes a liability when people think they’re out of the way when they’re not,” Cairo said. “As with many charts, it’s risky to assume that we can correctly interpret a hurricane map at a glance. Graphics like these need to be read accurately and carefully. Only then can we understand what they are really saying.”

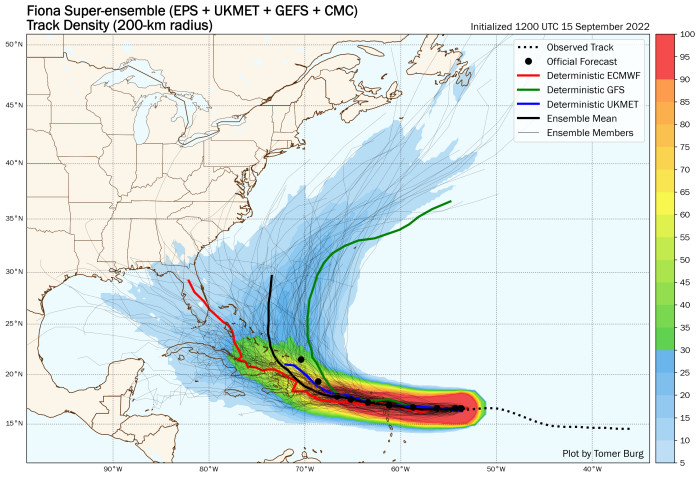

Another recently popular way of visualizing the possible tracks of the hurricane is called the spaghetti model.

Spaghetti models show a combination of different model ensembles. The map below shows a multi-model ensemble combining long-term forecasts from the Global Ensemble Forecast System, the Canadian Meteorological Centre, the UK Meteorological Office and the European Copernicus Service.

The short-term forecast is quite confident, many of the models agree, but they soon diverge quite a bit, showing how difficult it can be to make long-term forecasts for hurricanes.

This format is great for showing uncertainty, but lacks key information about the size and strength of the hurricane.

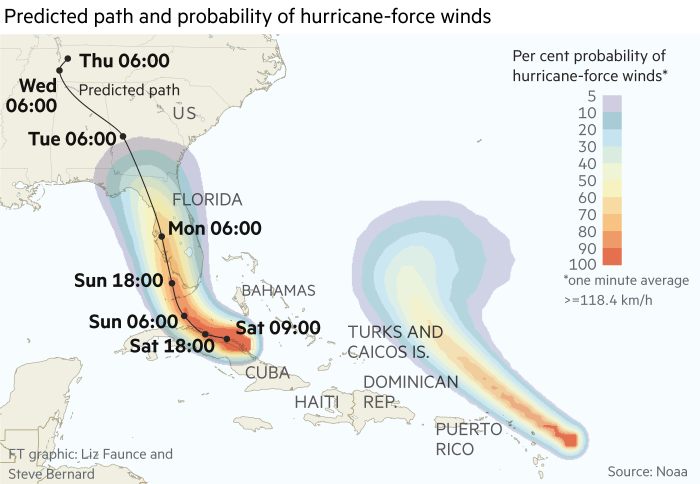

The NHC creates many charts for each tropical storm it names. At the Financial Times we prefer to show the likely path and probability of encountering gale force winds (> 118 km/h or 73 mph). This combination highlights the dangers of the hurricane more clearly than the Cone of Uncertainty and Spaghetti Model cards individually.

climate capital

Where climate change meets the economy, markets and politics. Discover the coverage of the FT here.

Curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Learn more about our science-based goals here