How to think about the unthinkable

News

1. Eleven new COVID deaths

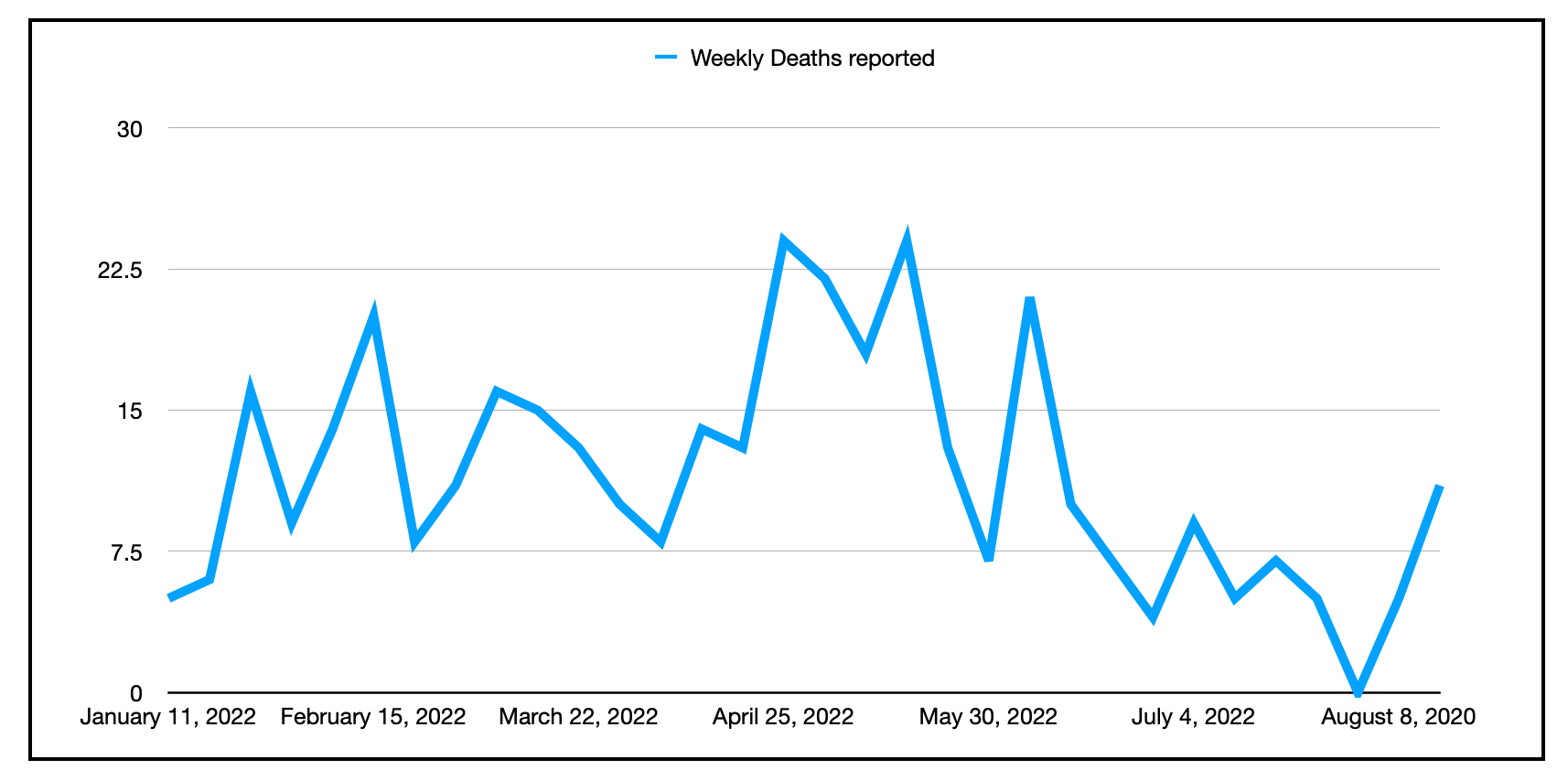

Weekly reported COVID deaths in Nova Scotia since January. Note that due to a change in the reporting period, the week ending April 11 has just six days.

Yesterday, the province announced 11 new deaths from COVID for the most recent reporting week, August 9-15. This is the highest weekly reported death count since June 8 (when there were 20).

I won’t have demographic data for, or the vaccination status of, the newly reported deaths until September 15.

Now we’ll play the death calendar game: some, maybe most, of the newly reported deaths are people who died some time before August 9, and the investigation, which takes some time, only recently revealed that those deaths were caused by COVID, so the current figures aren’t as bad as they seem.

But this is disingenuous; when the reported weekly death count is low, that’s seen as progress, but when it’s high, those deaths are shuffled backwards on the calendar to the weeks when the death count was low, and we gloss over the past celebration of progress. Still, deaths are deaths, and now Nova Scotia is up to 484 COVID deaths in Nova Scotia.

Also, 40 people were admitted to hospital because of COVID in the most recent reporting week.

Nova Scotia Health reports the current hospitalization status as:

• in hospital because of COVID: 50

• in hospital for something else but have COVID: 127

• caught COVID in hospital: 94

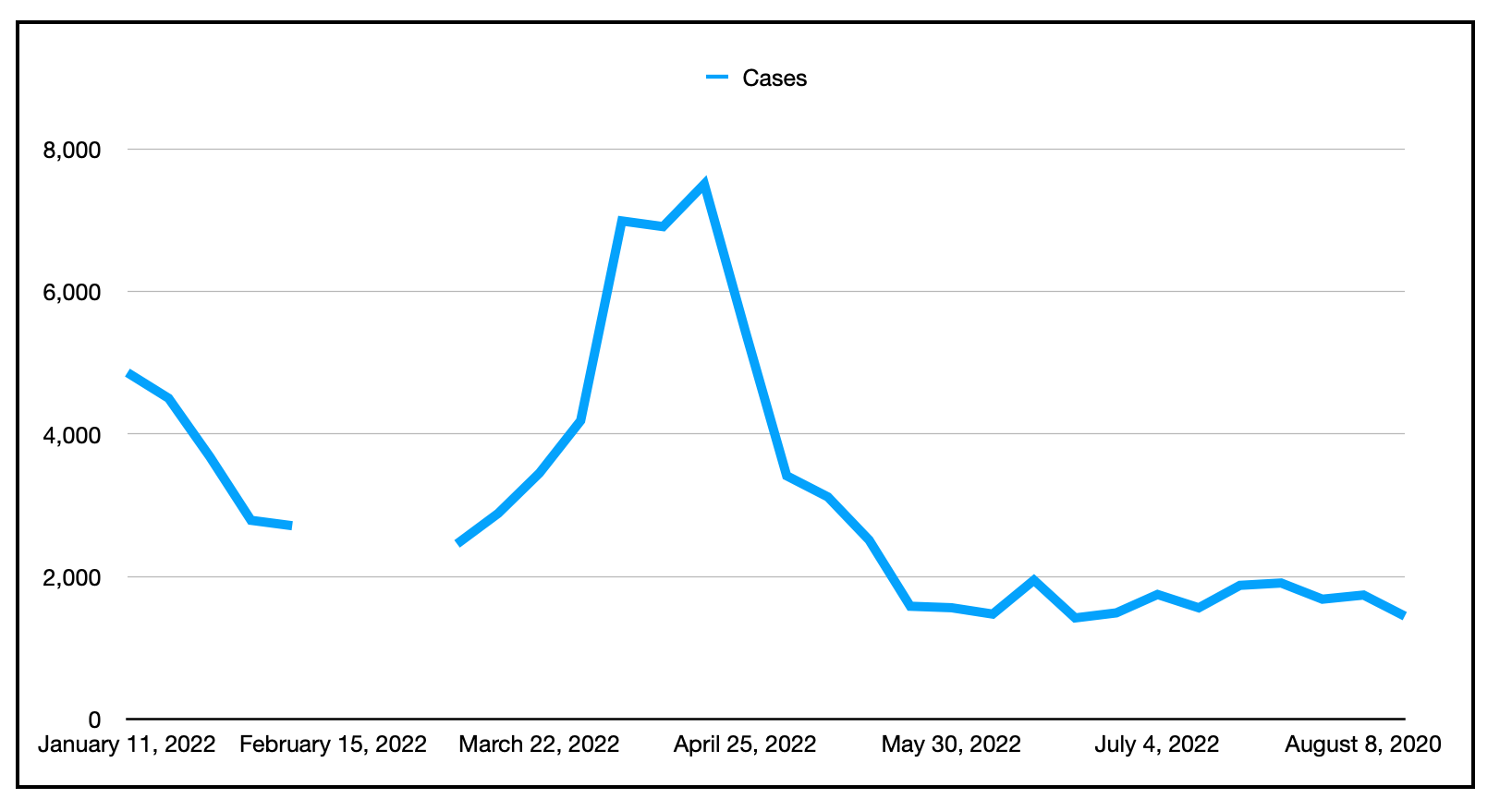

Weekly lab-confirmed (PCR tests) new cases since January. The gap reflects a temporary change in testing protocol that makes weekly comparisons meaningless. Note that due to a change in the reporting period, the week ending April 11 has just six days.

Additionally, for the reporting period, there 1,445 new lab-confirmed (PCR tests) cases, which is the lowest weekly count since June. But I take that decline with a grain of salt: The weekly new case figure does not include people who tested positive with only a rapid take-home test, or those who didn’t test at all.

And why should anyone much bother to get a PCR test anyway? I’ve lied in order to get a PCR test — people close to me are at very high risk for severe outcomes from COVID, and before I visited with them, I wanted to be as sure as possible that I wasn’t carrying the virus, so said I had symptoms I didn’t have so I was eligible for a PCR test. I feel bad about lying in order to be a good citizen, but here we are.

I know other people are making such convoluted decisions, but why should most people get tested at all? If you test positive, you don’t actually have to do anything — you can go about your usual business maskless if you want. I suspect most people aren’t quite so callous, but if they test positive with a rapid test they just stay home until they no longer test positive, and they never get a PCR test.

Point being, we really don’t have any idea how much COVID is out there. (Yes, wastewater sampling, but those are just general indicators, and only cover the areas serviced by the three sewage plants being sampled, missing most of the province.)

(Copy link for this item)

2. Old growth forests

A stand within the community-proposed Ingram River Wilderness Area. It contains a 400 plus eastern hemlock tree. Photo courtesy Mike Lancaster

“Effective [yesterday], old-growth forests in Nova Scotia will be protected from logging or other commercial activity under an updated old-growth forest policy,” reports Jennifer Henderson:

The policy takes effect four years after being recommended to government by an independent forestry review led by University of King’s College president Bill Lahey. Natural Resources and Renewables Minister Tory Rushton made the announcement on Thursday at a joint federal-provincial news conference held to announce commitments to preserve more land and help reduce carbon emissions to fight climate change.

Click here to read “Old-growth forests in Nova Scotia finally get protection.”

(Copy link for this item)

3. Parks

Caitlin Grady, conservation campaigner with the Nova Scotia chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, and Chris Miller, CPAWS Nova Scotia’s executive director, left, hike along the shore of Charlie’s Lake in the Blue Mountain-Birch Cove Lakes area on Thursday, July 15, 2021. — Photo: Zane Woodford

“Representatives from the Nova Scotia Nature Trust, Friends of Blue Mountain, and the Nature Conservancy of Canada were on hand Thursday when federal Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault made an announcement with his provincial counterpart promising to protect more of Nova Scotia’s land and biodiversity,” reports Jennifer Henderson:

The two levels of government have committed to several initiatives :

- to advance negotiations on a funded Nature Agreement that will include protecting more natural spaces in Nova Scotia and increasing habitat protection for species at risk and migratory birds, to be finalized by 2023

- complete the pre-feasibility assessment and work toward the designation of the Blue Mountain-Birch Cove Lakes area as Canada’s first urban wilderness park, together with the Halifax Regional Municipality, the Nova Scotia Nature Trust, and the Nova Scotia Mi’kmaq. The federal government has committed to making a major investment, either land acquisition or infrastructure, by the end of 2023

- develop a funding agreement to conserve Old-growth Forests and address the hemlock woolly adelgid (an invasive pest). Under the Nature Smart Climate Solutions Fund, Environment and Climate Change Canada has agreed to commit up to $10 million which will contribute to reducing greenhouse gas emissions and increasing carbon sequestration

- seek new opportunities for connecting key areas of protected and conserved lands, including completing a pilot project under Parks Canada’s National Program for Ecological Corridors by 2025, in collaboration with partners

Click here to read “Feds, province announce agreements to create urban park, conserve land.”

(Copy link for this item)

4. Those French have a different word for everything

From the cover of the FFANE’s newly launched French language caregivers guide.

“At least one in three Nova Scotians are unpaid caregivers, and a new guide launched this week will help those who provide that care in French,” reports Yvette d’Entremont:

“When you’re looking for support, when you’re looking for answers in stressful times, it’s so much better to have it when you’re not struggling to understand the language on top of navigating government systems,” Élizabeth Vickers-Drennan, project coordinator for the Fédération des femmes acadiennes de la Nouvelle-Écosse (FFANE) said in an interview on Thursday.

The resource, titled ‘Guide de la personne aidante’ (Caregiver’s Handbook), was launched on Monday by the FFANE, a non-profit organization that promotes the personal and social development of Acadian, Francophone, and French-speaking women in Nova Scotia.

Click here to read “New handbook provides guidance to caregivers in French.”

(Copy link for this item)

5. Thinking about the unthinkable

I’m on vacation.

And boy howdy do I need this vacation. I’ve been burned out for a while, but these past two years have been relentless, with the pandemic and then the Nova Scotia mass murders taking all of my time, attention, and emotional space, and then some. Reporting on the Mass Casualty Commission has about broken me, so when the commission took a summer break, I (mostly) turned off the computer, and hit the road.

It’s the closest thing to an honest vacation I’ve had since I started the Examiner eight years ago, and it speaks to the exceptionally capable Examiner crew taking care of the shop in my absence. Writing an abbreviated Morning File (which is now so late I need to call it a Vacation File) and a couple of COVID updates aside, I’ve (mostly) been successfully not-working for the past two weeks, spending the bulk of my time visiting family and friends, camping, going to the beach, exploring the Smithsonian, and sleeping.

And reading. Before I hit the road, I stopped by Bookmark and picked up a handful of books, including this one I got from the remainder shelf for five bucks:

You may know author Bill James as a subject of the Michael Lewis book Moneyball. The subsequent Aaron Sorkin film of the same name writes James out of the story, but James’ story is compelling; if you don’t have time to read an entire book about it, an episode of Lewis’s podcast Against the Rules profiles James. (I very much want to like Michael Lewis, but his friendship with Malcom Gladwell gives me great pause, a fact that James would have much to say about, I think.)

Here’s the shorthand version, as I remember it: James was working as a security guard in a pork and beans factory, a do-nothing job that gave him time to think about his favourite game, baseball. He realized that sports analysts were going about it all wrong, and so started writing down his own thoughts, first on photocopied pages he self-published, which eventually morphed into the baseball bible, The Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract. James’s insights have completely changed professional baseball.

Just a tiny piece of James’s insights: errors are meaningless. First of all, they are subjective — someone sitting in a booth somewhere has to make the call. Besides that, errors fault a player for things that aren’t completely in his control — a pitcher throws a rotten pitch, so the batter is able to hit a line drive that the shortstop can’t handle; why is the shortstop penalized? And errors are ascribed to players who almost make the play, but not to players who can’t even get into position to almost make the play in the first place. It’s a terrible stat.

James’s overall philosophy: emotion has to be taken out of analysis. Tradition can’t be trusted, and what you “know” might be your worst enemy.

James evidently now has the time to look at things that aren’t baseball, and so noticed a string of mass murders in the 1909-1912 in the American midwest, which involved entire families killed while they slept by the blunt end of an axe.

Even at the time, people were suspecting a serial killer, but James thought there was more to it, so he hired his daughter, Rachel McCarthy James, as a researcher, and together they culled through historic newspapers, census records, and court documents and came up with a startling theory: there was one man responsible for not just the 1909-12 murders, but for a string of over 100 murders dating back to 1898.

One of the murdered families James looks at was in Nova Scotia, in Dominion — the 1906 murder of Anton Stretka, his wife, and a four-year-old boy and two-year-old girl. James couldn’t find the wife’s and children’s names; I suppose if I wasn’t on vacation I could take the time to dig into that, but I’ll let that ride for the moment. James isn’t entirely convinced that the Stretka murders are part of the broader series, but the similarities are so striking that he felt compelled to mention them.

The Jameses purport to solve the case, which I take to mean they’ll name the killer. I’m today on Chapter 38 of the book, page 413 out of 460, and haven’t yet gotten to the “solving” part, but I’ll let you know, after I finish.

Is it weird that I’m taking a break from the emotionally exhausting reporting on the Nova Scotia mass murders by reading a book about mass murders? Probably. I do a lot of weird shit. But distance has its benefits. The Black Death of the 14th century was about as terrible event as can be imagined — the misery is unfathomable, but 700 years later, we can make jokes about it and no one is offended. We talk about past wars, even wars people who are still alive experienced firsthand, as if the wars were just another iteration of the board game Risk, a child’s game, concentrating foremost on strategy and weaponry and such, while we gloss over the deaths and trauma of millions of people.

The trail of death James chronicles is likewise terrible. These were real people, with dreams and aspirations, they had people they cared about, jobs and families they valued. Loved ones were traumatized (James does a good job describing the emotional toll and mental illness experienced by the families and friends of the victims). But, well, it’s not our problem. These are people who lived a long time ago, and the families and friends are long dead. The space of time allows us to view those old murders with detachment, and we can assess them without the burden of our own emotions.

An aside. James is a very good writer, and this surprised me. My own bias is that a guy who thinks abstractly about statistics all day long can’t possibly be a good writer, but subject matter aside, this is fantastic writing. James has an ease of storytelling that makes you want to re-read chapters just to experience the fun of it again. Here’s how he opens Chapter 20:

When Bob Hensen visited the Van Lieu family on November 6, 1900, he brought them a chicken. I am certain they didn’t ask where he got the chicken. The Van Lieu family were honest, upstanding, hardworking people. Hensen, on the other hand, was infamous, notorious. Which is worse, infamous or notorious? Whichever one was worse, that was what Hensen was. The newspapers would say that he had a bad reputation. He had a bad reputation in the same sense that Michael Jordan had a jump shot.

Spoiler: James doesn’t think Bob Henson killed the Van Lieus. He writes:

The case against Hensen is poor, and it rather sets my teeth on edge when people decide who committed a crime in the first twenty minutes of the investigation.

All the same, Hensen was executed for the crime.

And it’s not just Hensen. James tracks a large number of wrongful convictions and, even more disturbing, at least six black men lynched for the murders that were likely committed by someone else. He points out that when there’s an unimaginable crime that happens — an entire family murdered, with no apparent reason — then it is the first instinct to blame the most marginalized among us:

What happens in many of these cases is that, in the absence of evidence, the crime is pinned on a person of low social standing who is known to be in the vicinity of the crime. We have seen this repeatedly. There was no evidence that Henry Lambert murdered the Allen family, but he was a person of low social status who was near the scene of the crime, and the state of Maine convicted him and locked him up for twenty years before admitting they had made a mistake. There is no real reason to believe that George Wilson murdered Archie and Bettie Coble in Rainer, Washington, but he was a person of low social standing who lived near the scene of the crime. He was bullied into a probably bogus confession and convicted of the crime. There is no evidence, really, that Reed and Cato murdered the Hodges family, but one of the two was bullied into a false confession, and then they were killed by a lynch mob.

There are others like that in this book, but you get my point. [emphasis in original]

If I have a quibble with James, it’s that while he does a good job of detailing policing failures, and that while he recognizes that cops and prosecutors framed people for unsolved murders, he doesn’t see the framing of innocent people as a pervasive and ongoing police methodology. The current-day literature on wrongful convictions is replete with police beating and torturing suspects in order to get false confessions out of them, but James writes it off as simple “bullying.”

Still, James approaches the mass murders with the same detachment he uses to analyze baseball: to understand what happened, we must become emotionally disconnected to the horrible crimes, we must not let our preconceptions drive the narrative, and we must not make connections when there are none.

James finds that time and again, people wanted to blame the woman of the murdered household for the fate that befell them. With no evidence at all, people said the women had loose sexual mores, or were having an affair that brought on the attack.

And: people made shit up. Often, immediately after the murders, entirely false narratives were created, and then as time went by, new false narratives replaced the old false narratives. People’s stories changed. People who said they didn’t see anything the day after the murder, two weeks later remembered that they did see something. A few hours after a murder, a witness reports that a stranger was lurking in the shadows; later, the same witness says the man in the shadows was the fellow up the street who the witness knew his entire life. Like that.

I think about the 2020 Nova Scotia mass murders. As was the case in the stories James chronicles, the 2020 mass murders involved real people, with dreams and aspirations; they had people they cared about, jobs and families they valued. Loved ones were and are traumatized. A community can’t make sense of it, because there is no sense to make of it.

And because we can’t make sense of it, we create false narratives. Even as the murders were ongoing, the common wisdom — which was entirely false — was that the bad people of Portapique had an illegal pandemic party that Saturday night, and that’s where all the people were killed. And in the wake of the unimaginable crime, many other false narratives were created, and a woman was falsely accused, again with no evidence.

We absolutely should create a narrative for the mass murders, but that narrative needs to be rooted in a truth that can be ascertained, not by making shit up.

(Copy link for this item)

6. Another woe-is-me restaurant story

I thought robots were going to solve the don’t-want-to-pay workers problem?

(Copy link for this item)

Government

No meetings

On campus

No events

In the harbour

Halifax

06:45: CSL Tacoma, bulker, sails from Gold Bond for sea

08:30: NYK Deneb, container ship, sails from Fairview Cove for sea

10:00: MOL Maestro, container ship, arrives at Fairview Cove from Colombo, Sri Lanka

10:30: MSC Veronique, container ship, sails from Pier 42 for sea

12:30: Paris II, container ship, arrives at Pier 42 from Sines, Portugal

18:00: John J. Carrick, barge, sails from McAsphalt for sea

19:00: Atlantic Condor, offshore supply ship, moves from Dartmouth Cove to Irving Oil

19:00: Oceanex Sanderling, ro-ro container, sails from Pier 41 for St. John’s

Cape Breton

No arrivals or departures.

Footnotes

I could get used to this.

Subscribe to the Halifax Examiner

We have many other subscription options available, or drop us a donation. Thanks!