Defensive Guitar: How to Trim the Fat & Stop Playing So Damn Many Notes

The interface between guitar and piano is omnipresent – and with it the potential for harmonic conflicts, especially when improvising. However, guitar and piano can be a wonderful combination. Listen to the recordings of Pat Metheny and Lyle Mays or Jim Hall and Bill Evans for standout examples. But if your ears aren’t perked up, it can be a recipe for disaster.

The paradigm that often applies at the music pavilion is that if the guitar and piano collide harmoniously, the guitarist is automatically to blame. How do we deal with that? There are a few methods of taking a more defensive approach, but we’ll cover learning which notes to omit. Trim those chords and be nimbler and stronger. Chords with more than two or three notes are bullseye for our purposes. The good news is that these lean chords are easy to play and sound a lot better in the context of the band than the ubiquitous barre chord.

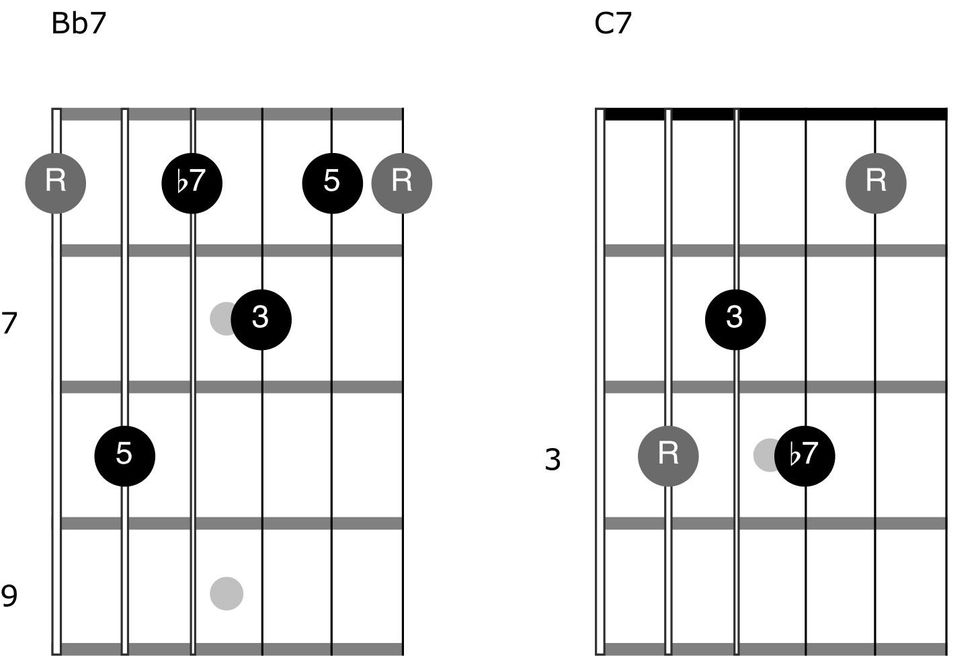

The basis of the chords we will consider are subsets of chords that you are probably already very familiar with (ex1)

The “money” in these chord shapes is literally in the middle of the chord. On the 3rd and 4th string are the 3 and 7 of the chords. These are the most important two notes of your chord. The different variations of the 3 and 7 give each chord its unique color, such as major 7, dominant 7 or minor 7.

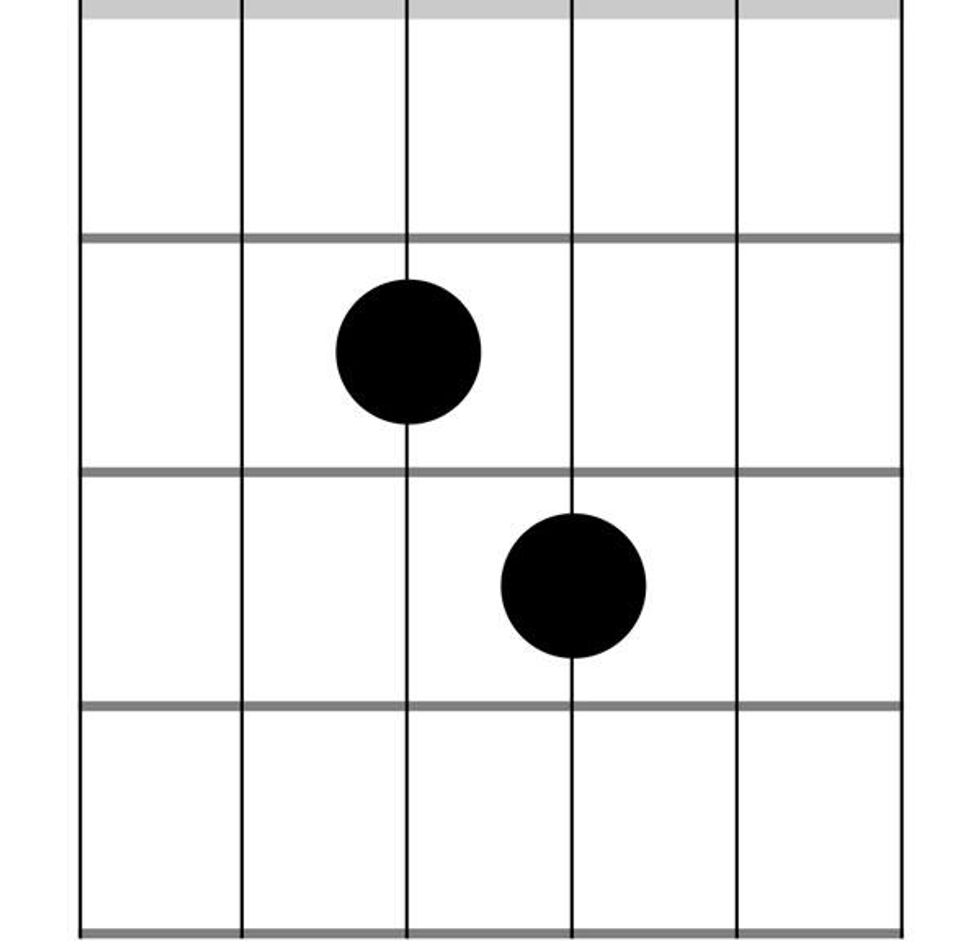

When we reduce these chords to their essence, we get the form inside ex2. This reduces the Bb7 to Ab and D while the C7 is simply the E and Bb. These notes are sometimes referred to as guide tones. We will move this shape up or down the fretboard to accommodate each chord quality required.

ex2

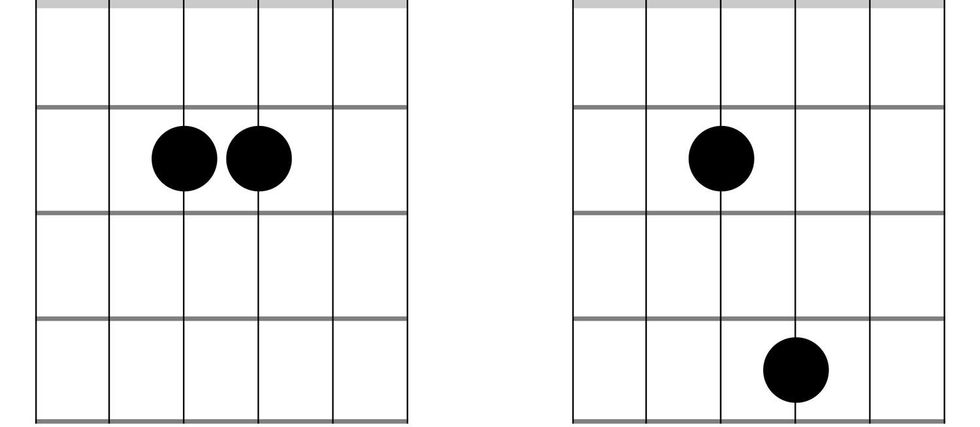

In addition to the tritone, we will only use two other interval forms. in the Ex. 3 You can see a perfect fourth on the left and a perfect fifth on the right. They’re super easy to play and extremely effective on our journey to more defensive guitar playing. Feel free to use any fingering that suits you.

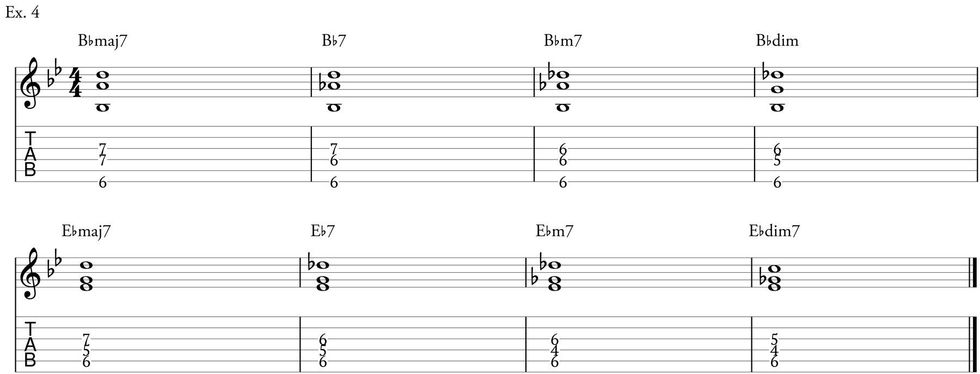

Let’s put these shapes in context. in the Ex. 4 You can see how these shapes work with a 6th string root (top row) and a 5th string root (bottom row). I added the root notes simply for reference and to help you visualize the shapes better. In a solo setting, you might even want to include the root notes.

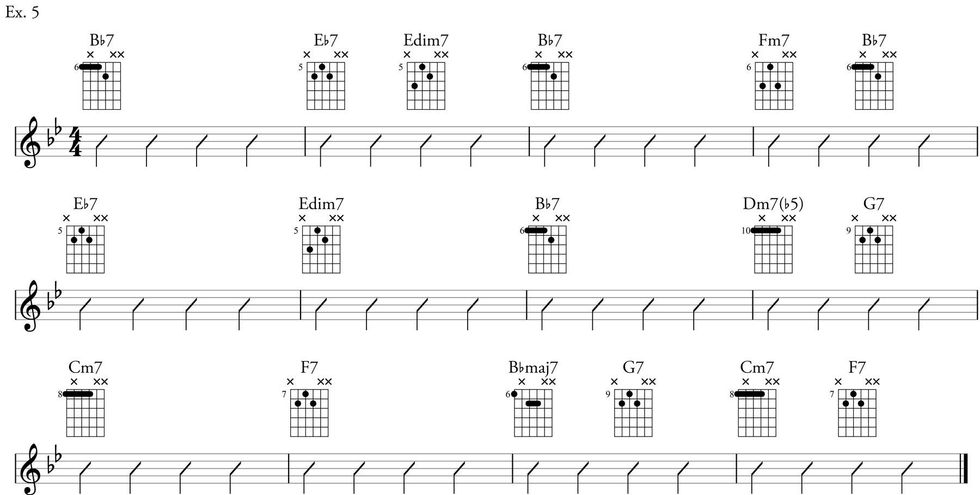

An excellent “closet organizer” for musical data is the 12-bar jazz-blues form. in the ex. 5 I use our core family of shapes to work through an entire progression. I made sure to include dominant, major, minor, and diminished chords in this example. The first step should be to play it with the root notes and then try to “hear” the root notes while only playing the leading notes.

The absolute undisputed king of this type of chord is Freddie Green, longtime guitarist for the Count Basie Band. He made a career of playing quarter note rhythms and being the glue that held the rhythm section together. in the item 6 You can, as Green might, play a 12-bar blues in Bb. Notice the chromatic movement in the last two bars. It’s amazing how smoothly you can connect the chords with just two notes.

Admittedly, the rhythm is a bit bland and seems sterile. in the Ex7 I play the exact same chords but add a bit of chromatic movement and some unconventional rhythms. The occasional overtime (9, 11, or 13) is cool, but choose your points wisely. Listen and search for the piano your Place.

The same concept can be applied to your single note improvisations as well. In fact, this is a valuable step in learning to overwrite changes. The goal is to outline the chords well enough for your ear to visualize the harmony passing by. in the Ex. 8 You can see how I might approach this. Note the lack of “blues licks”.

While it always looks cool on your IG page when you’re seen playing stretchy Alan Holdsworth-esque chords, sometimes it’s the simple and economical approach that resonates best. Whether you’re performing behind a singer, playing with a jazz big band, or playing chords and walking bass Joe Pass style, the defensive approach to harmony can often be your ticket.