Louis-Schmeling II, 85 years later, remains the most significant sporting event of the 20th Century

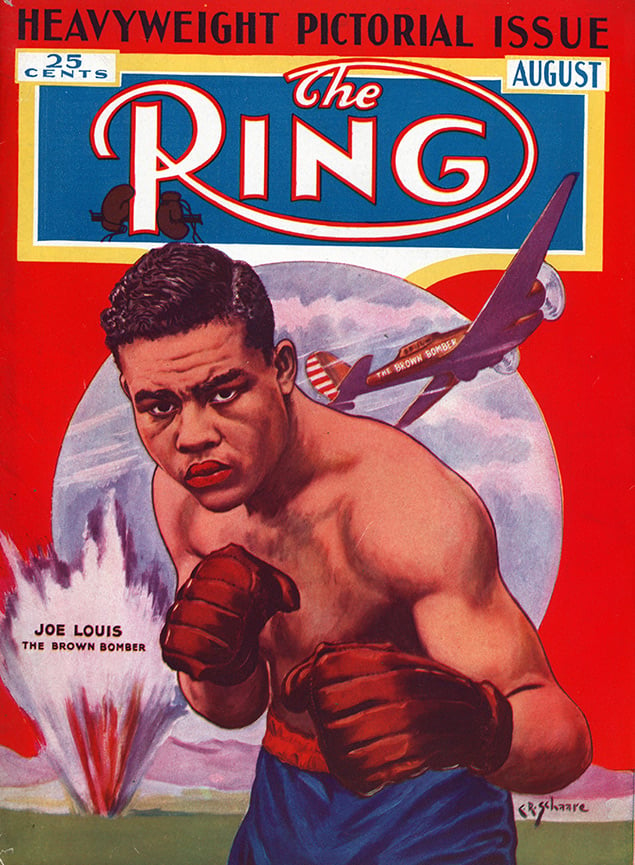

With the weight of the world on his shoulders, Joe Louis rose to the occasion like no other athlete had ever accomplished prior to his rematch with Max Schmeling. Photo from the Ring Archives

By 10 p.m. on the night of June 22, 1938, the streets of America were deserted. Over 60 million Americans, more than half the population of the country at the time, sat glued beside their radios waiting to learn if democracy would prove superior to the Nazi regime that now ruled Germany and soon would sweep across most of Europe.

Such was the weight on the 24-year-old shoulders of Joe Louis as he waited to slip between the ropes at Yankee Stadium to face Max Schmeling, the only man who had ever beaten him. Arguably no athlete in history had ever faced such a challenge and no sporting event before or since ever carried with it such massive geopolitical meaning.

This was, in one sense, just a prize fight but in reality, its significance loomed so much larger that it was not really a prize fight at all. Nor was it simply a young man trying to avenge his only defeat. In the words of one Boston sportswriter of the time the fight was far bigger than anything any athlete had ever faced before.

“Louis represents democracy in its perfect form: the Negro who would be permitted to become a world champion without regard for race, creed or color,” the writer wrote. “Schmeling represents a country which does not recognize this idea or ideal.”

Former heavyweight champion Joe Louis, the most iconic fighter of the 1930s and ’40s (arguably of the 20th Century), was born on May 13, 1914.

The truth was that weight bore just as heavily upon the shoulders of Max Schmeling, the former heavyweight champion who had knocked Louis out two years earlier and against his will and personal beliefs become a symbol of the Nazi ideal of racial purity. Like Louis, Schmeling was an athlete not a politician but with a world war on the horizon few saw either solely in that light any longer.

Hammering home that point, “The Angriff,” the newspaper mouthpiece of Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels, wrote the day of the fight: “On this day two men will hold an entire world in the utmost tension.”

With the Nazis preparing to launch an attempt to destroy the Jewish race, two prize fighters had come to New York not merely as boxers but as symbols of polar opposite political and social systems. Over 20 million Germans rose in the middle of the night to listen to the 3 a.m. radio broadcast of the fight while over 2,000 of their countrymen had crossed the Atlantic in massive ocean liners, sailing past the Statue of Liberty into New York harbor with Nazi swastikas rippling in the wind from the liners’ masts.

Germany saw Schmeling as not simply a superior boxer to Louis but as a superior man. He was viewed, unfairly it came to be known later, as the flag bearer for Nazi supremacy, a towering symbol of what Hitler called his “master race.”

In truth Schmeling was no Nazi. He never joined the Nazi party and in fact would secretly hide two young Jewish teenagers in his home five months later during Kristallnacht, the night when brown shirted Nazis destroyed Jewish homes, synagogues and businesses throughout the country, signaling the end of any semblance of normal Jewish life in Germany.

Just before midnight on November 9, Gestapo chief Heinrich Müller sent a telegram to all police units in Germany informing them that “in shortest order, actions against Jews and especially their synagogues will take place in all of Germany. These are not to be interfered with.” Rather, the police were instructed to arrest the victims. Fire companies stood by as synagogues went up in flames with explicit instructions to let them burn. They were to intervene only if a fire threatened Aryan-owned properties.

In just two nights, more than 1,000 synagogues were burned or otherwise damaged. Rioters ransacked and looted about 7,500 Jewish businesses, killed at least 91 Jews, and vandalized Jewish hospitals, homes, schools, and cemeteries. The attackers were often neighbors. Roughly 30,000 Jewish men aged 16 to 60 were arrested and sent off to concentration camps at Dachau, Buchenwald and Sachsenhausen.

Those actions came to symbolize the destruction of Jewish existence in Germany and put at risk Germans like Schmeling, who had agreed to hide away the teenaged sons of two Jewish friends, very likely saving their lives while putting his own at risk. Only years later, long after the Nazis had been defeated in World War II, did Schmeling’s actions come to light. That would give the world a different view of him than existed on June 22, 1938, the night that turned Joe Louis from a boxer into an American icon.

Schmeling, both by temperament and necessity, had chosen to walk a tightrope between Nazi symbol and non-political athlete. After his stunning knockout of Louis two years earlier. Hitler was so elated he sent flowers and a private message of congratulations to Schmeling’s wife “with all my heart.” In response, Schmeling told a German newspaper reporter “At the moment I have to tell Germany, I have to report to the Fuehrer in particular, that the thought of all my countrymen were with me in this fight, that the Fuehrer and his faithful people were thinking of me. This thought gave me the strength to succeed in this fight. It gave me the courage and the endurance to win this victory for Germany’s colors.”

Max Schmeling returned to Berlin to a hero’s welcome after upsetting Joe Louis via 12th-round stoppage in New York City on June 27, 1936. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

It was not exactly an endorsement of the Nazi philosophy but a statement that could be interpreted however one chose. It led the Nazis to embrace Schmeling and most Americans to be repulsed by him.

Schmeling believed that victory would lead to a title shot against James J. Braddock but that went to Louis as much for political reasons as boxing ones. Many boxing officials feared if Schmeling won Hitler would not allow him to defend it against American fighters. With the heavyweight title being the biggest producer of revenue in the sport that was a situation no one outside of Germany would allow so Louis got the shot on June 27, 1937, knocking out Braddock in the eighth round. Ever the gentleman, Louis said after the fight he would not recognize himself as champion until he defeated Schmeling.

After much back and forth negotiations by Schmeling’s manager, Joe Jacobs, and New York boxing promoter Mike Jacobs, who were ironically both Jewish, the fight was made. By then Germany had already annexed Austria and throughout Europe the winds of war were howling.

Schmeling had been urged by Jack Dempsey to defect to America but he refused. Despite personally defying Hitler’s claims of racial superiority by saying, “I am not a superman in any way” Schmeling remained a loyal German at a time when lines were being drawn around the world.

Regardless of his politics, Schmeling did become friendly with Goebbels, whose mastery of propaganda fueled the rise of the Nazis and Schmeling’s place as a symbol of their beliefs. Not surprisingly Schmeling was greeted in New York with barely hidden hatred by the bulk of American fight fans.

There were pickets outside his hotel, the Anti-Nazi League demanded a boycott of the fight and a goodly number of sportswriters – but not all – portrayed him in the worst light. At the same time Joe Louis was meeting with President Franklin Delano Roosevelt at the White House. Louis would later write in his autobiography that “I had my own personal reasons (for wanting to defeat Schmeling) and the whole damned country was depending on me.”

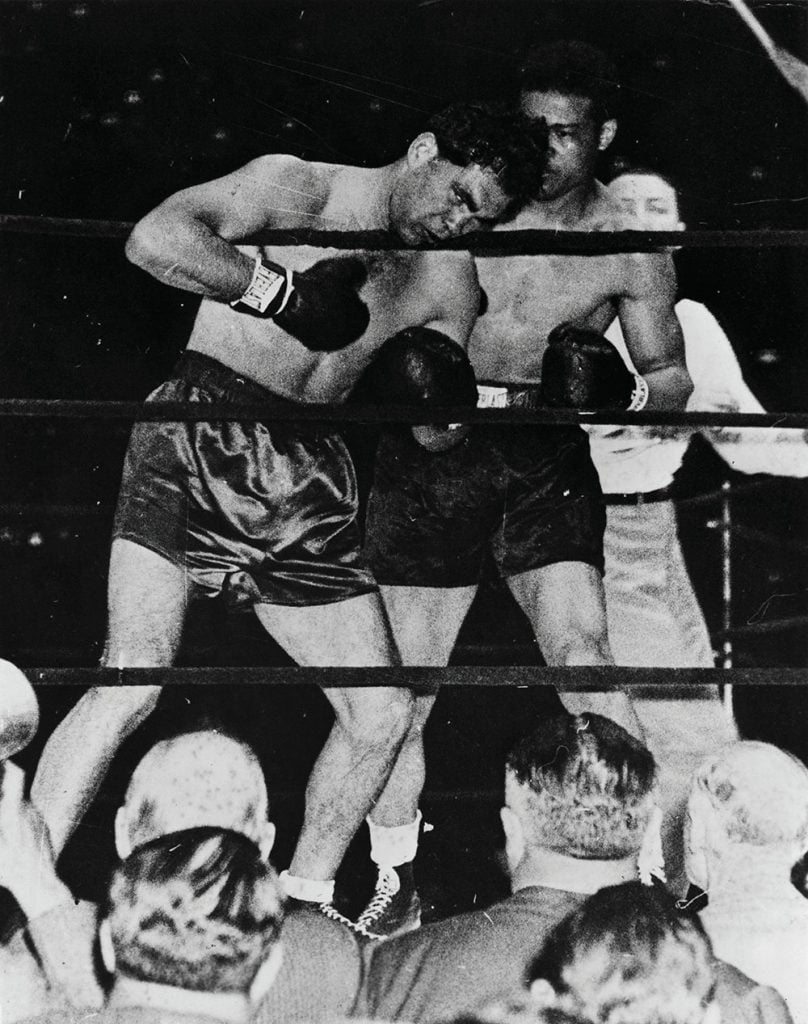

What Schmeling was depending on was exploiting a fistic flaw he’d noticed before their first fight – a lazy left jab that left Louis vulnerable to counter right hands because he was slow to bring his left back into defensive position. Schmeling beat Louis down with counter rights all night, dropping him for the first time in his career in the fourth round and finishing him in the 12th with two sizzling right hands that left him face down on the floor as he was counted out. Americans, both black and white, wept that night.

Now an improved Louis would get his chance for revenge in a fight heavily laden with political overtones. Unnoticed by Schmeling was that Louis had corrected that flaw. Now waiting for him in front of 70,043 spectators at Yankee Stadium who had paid $1,015,012 to get in (the equivalent of over $20 million today) stood perhaps the greatest heavyweight who ever lived.

Yankee Stadium was filled to capacity for the Louis-Schmeling rematch. Photo from The Ring archive

At 24, Louis was at the height of his considerable powers while the 33-year-old Schmeling was in decline, not that it would have mattered. There was little Schmeling could have done that night to stop Louis, who needed only 124 seconds to destroy the myth of Aryan superiority.

Barely 90 seconds into the fight, referee Arthur Donovan stopped the action after Louis had battered Schmeling with a barrage of five left hooks and a crushing punch to the kidney that fractured the transverse process of the third and fourth lumbar vertebrae. In other words, the punch had broken his back. When it landed sportswriters at ringside were shocked to hear Schmeling cry out in agony as his head slumped onto the top rope.

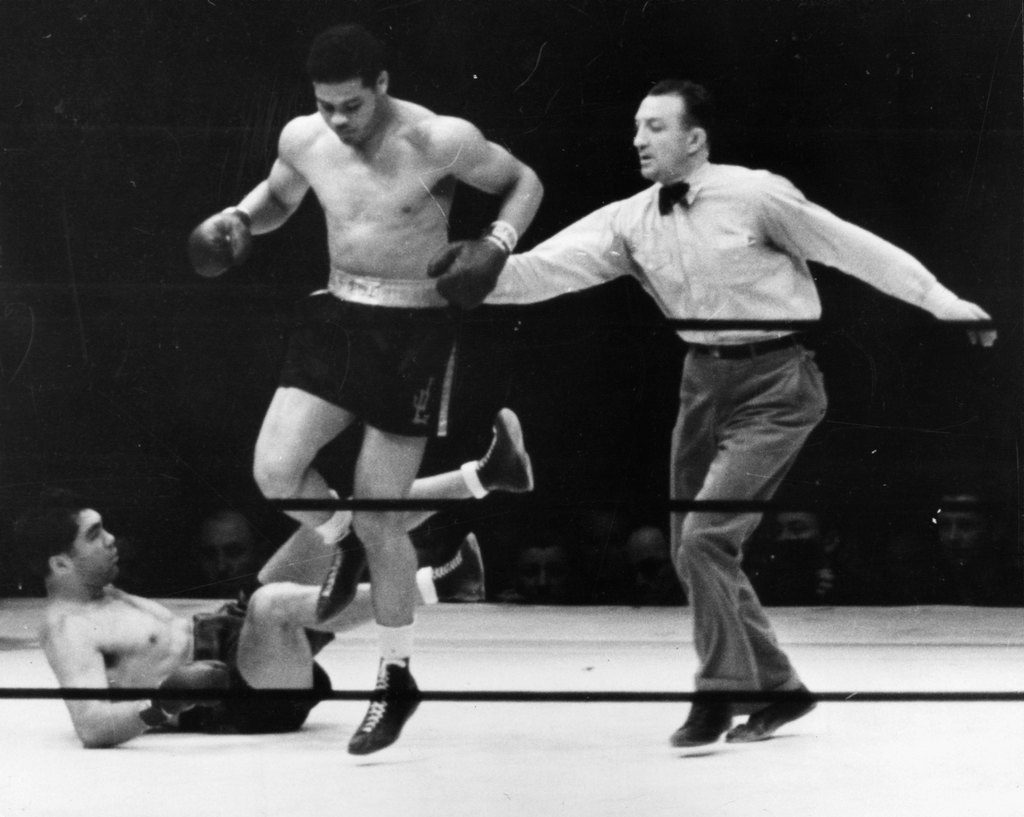

Louis emerged from the neutral corner at Donovan’s signal to resume fighting and attacked Schmeling with a viciousness few had previously witnessed. He knocked Schmeling down with a slashing right hook to the face. Schmeling rose at the count of three, a man adrift in an angry sea of leather.

Louis sent him down a second time and within seconds again dropped the towering symbol of German superiority. As Donovan began his count, Schmeling’s trainer, Max Machon, threw in the towel although that flag of surrender carried no weight in New York.

As Donovan continued his count, Machon leapt into the ring, forcing Donovan to wave his hands over the fallen German. The fight was over at 2:04 of the first round.

Joe Louis wasted no time in decking

Max Schmeling during the opening round of their anticipated rematch. Photo from The Ring archive

The next day Frank Marshall Davis of the Associated Negro Press wrote, “It was the triumph of a repressed people against the evil forces of racial oppression and discrimination condensed – by chance – into the shape of Max Schmeling.”

Noted sportswriter Heywood Hale Broun opined, “And 100 years from now, some historian may theorize, in a footnote at least, that the decline of Nazi prestige began with a left hook delivered by a former unskilled automobile worker who had never studied the politics of Neville Chamberlain.”

Less poetically perhaps, bootblacks were offering a Joe Louis shoe shine. It only took two minutes and four seconds.

Sitting at home at 80 Shanley Avenue in Newark that night was eight-year-old Jerry Izenberg, a passionate baseball fan who would go on to become one of the country’s most influential sports columnists, defending and befriending Muhammad Ali throughout his life and supporting the fight for racial equality that for him began that evening. In his newly published memoir about growing up as a Jewish sports fan in the 1930s, “Baseball, Nazis and Nedick’s Hot Dogs”, Izenberg recalled his feelings that Thursday night as he sat with his family listening to Clem McCarthy’s call of the fight on NBC Radio.

“It was history, politics and Hitler that motivated (his father’s) explanation to me and my sister,’’ Izenberg said of his father’s insistence they stay up late on a school night despite the protests of their mother. “He told us about the Nuremberg laws of 1935, which was the start of Hitler’s isolation, persecution and eventual murder of Jews. At supper that night, there was no talk of Hank Greenberg or anything else baseball.”

Izenberg recalled his father telling his mother, “This is a more important lesson for them (than anything in school). Joe Louis is a colored man. He is fighting for all the colored people in this country. More than that, he is fighting for us Jews because Schmeling is representing Hitler. My old man was very wrong about that last.

“There was no doubt that night as we gathered in the living room around the radio that the fists of Joe Louis would be the fists of David, who in Biblical times went against Goliath with just five smooth stones… “This was a fight that both fed and divided the emotions of America. It was us against them.”

After it was over, Schmeling was taken to Polyclinic Hospital where he remained for several weeks, a man broken in body and spirit. Initially Schmeling complained that the decisive punch to his kidney that shattered his back was illegal but he quickly backpedaled from that. Hitler had no public comment but would later come to resent Schmeling’s quiet resistance to supporting the Nazi cause and had him drafted into the Luftwaffe as a paratrooper late in the war. He faced minimal combat, primarily visiting German troops to lift their morale until he was arrested by British soldiers in 1945 in northern Germany.

Ironically the route the ambulance took to deliver Schmeling to the hospital on June 22 wended its way through Harlem. Out the window Schmeling later claimed he saw hundreds of black Americans dancing in the streets, bands playing as they hollered Louis’ name.” They were not alone in their jubilation, as Izenberg recalled.

“All through the fight my dad was on his feet, throwing punches and hollering,” Izenberg wrote. “So was I.”

Has any prizefight held more social and historic significance than Joe Louis’ one-round destruction of Max Schmeling? Writers are still fascinated by Louis.

Twenty five years later a black man in Grambling, Louisiana told Izenberg he had reacted the same way, confirming for the writer what he knew the fight had meant to all Americans, but specifically Jews and people of color.

“Decades later, I still think about that night when miles apart, a white man and a black man who had never met, my dad and Calvin Wilkerson, shared a hero. ‘I never met your daddy but on that night we were brothers under the skin,’” Izenberg quoted Wilkerson saying.

Louis became a national hero and remained one for the rest of his life but ended up broke and hounded by the IRS for back taxes until his death.

Schmeling never fought for the heavyweight title again but in 1947 was cleared of the “Nazi-taint” by a British led “de-Nazification’’ court. He had a brief and unsuccessful return to the ring before retiring in 1948 at the age of 43. After the war he became a symbol of the so-called “good German” who had resisted the Nazis. Eventually he was awarded a lucrative Coca-Cola distributorship in Germany by James Farley, the former head of the New York Boxing Commission and a Coke executive that made him a multi-millionaire.

In 1989, during a tribute to Schmeling in Las Vegas, Henri Lewin, owner of the Sands Hotel and Casino, revealed he was one of the young boys Schmeling had hidden during Kristallnacht.

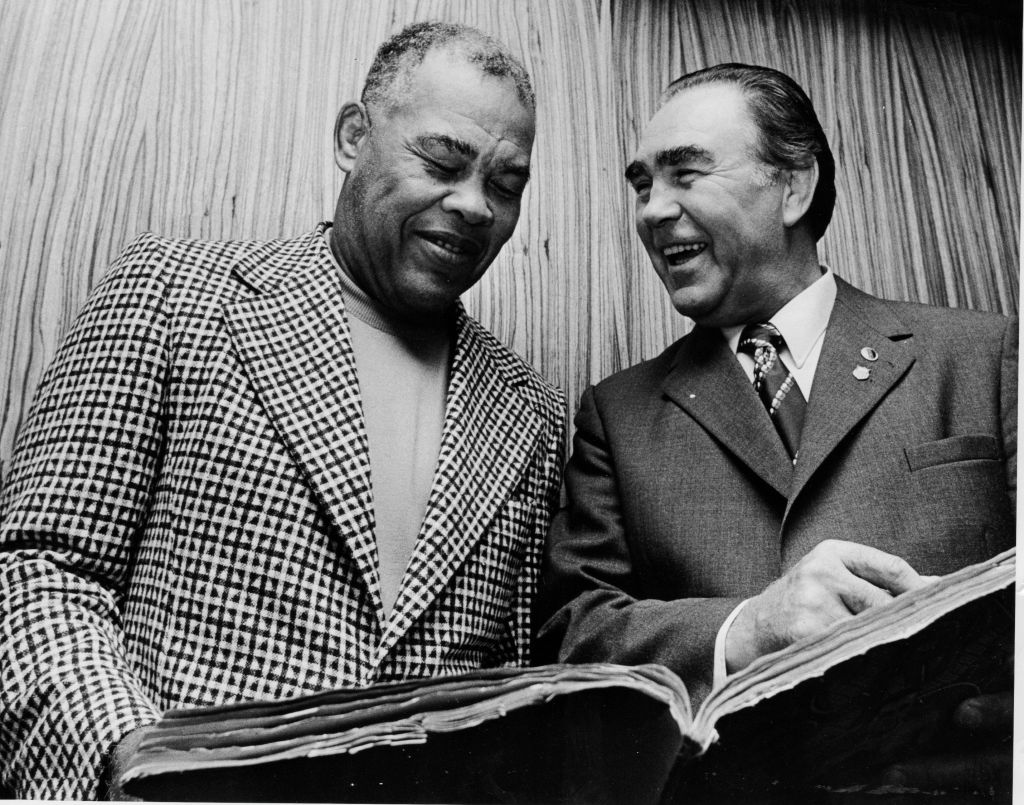

Years earlier Schmeling met Louis in a Chicago nightclub and began to explain he was never a Nazi. Louis cut him off saying, “Max, there’s nothing to explain. We are friends. It is all over.”

Joe Louis and Max Schmeling remained friends for the rest of their lives.

Louis and Schmeling reminisce over a scrapbook at the Nassau Coliseum in Uniondale, N.Y., on August 9, 1973. (Photo by David L. Pokress/ Newsday RM via Getty Images)