The ancient sport of falconry is alive and well in Utah

Estimated reading time: 6-7 minutes

SALT LAKE CITY – Falconry, the sport that uses highly trained birds of prey to hunt game, was inscribed on the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2010. The organization also recognized the archaeological work at the time, Say Chuera in Syria, that it may have uncovered the oldest depictions of falconry, dating back to around 3000 BC. are dated

Migratory falcons were first caught in the arid Middle East, and their presence as trained hunting companions greatly facilitated foraging in these desert regions. According to Britannica, Crusaders and traders from Europe and Britain brought the sport home after being exposed to it in the Middle East.

Hunting with eagles is still a tradition, passed from parents to children, in the Altia mountain range, which borders Mongolia and Kazakhstan. Early explorer and merchant Marco Polo documented Genghis Khan’s falconry expeditions in this region.

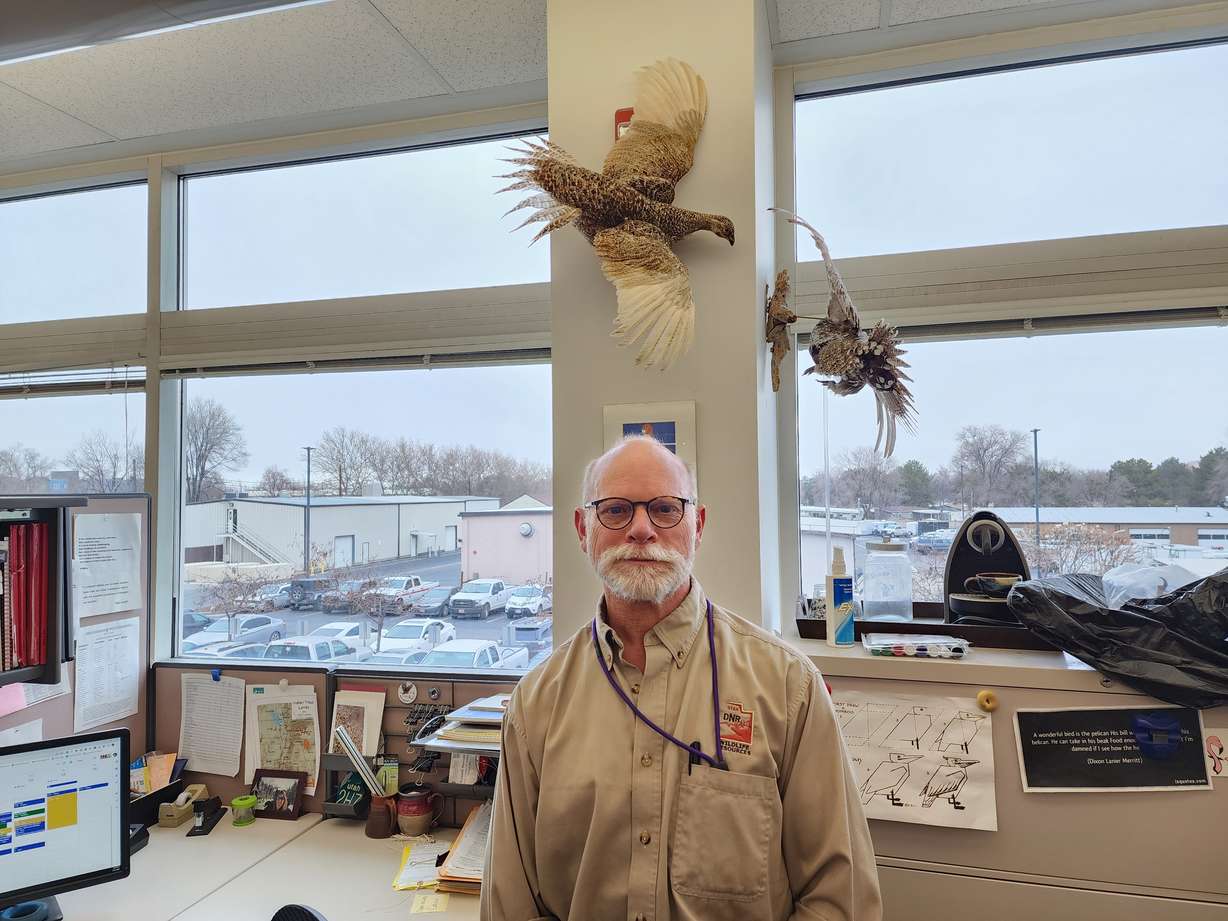

Russell Norvell, bird conservation program coordinator for the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, said Utah is home to about 375 active licensed falconers. Falconers in the United States are subject to both federal and state licensing and training requirements.

Utah’s requirements virtually mirror those of the federal government, although Utah allows the use of a wider variety of raptors than most states, Norvell said.

In addition to the licenses required to own raptors, Utah falconers also obtain the same hunting licenses as those who date bows, shotguns, and rifles. Falconers hunt everything from wild birds like ducks and sage grouse to upland mammals like rabbits.

Unlike in some parts of the world where falconry provides for families, falconers in Utah tend to use their quarry to feed their birds between hunts.

Breeding of birds of prey and mentoring of future falconers

While captive-bred raptors are widespread today, the practice of taking birds from the wild still exists in Utah and elsewhere, although these birds are considered to be on public loan rather than private property.

It is illegal to capture adult birds, so juveniles and birds up to 1 year old are usually sought. Mortality rates among young raptors are high, so capturing these birds is believed to be a win-win for both the captured bird and the remaining birds still in the care of their parents, according to Norvell.

“We, the Department of Wildlife Resources, are charged with the care, monitoring and management of Utah’s wild resources. Because a wild-caught bird retains its public property, in a sense we are lending it to a falconer who is qualified and responsible for making sure it is well cared for and well fed,” explained Norvell.

On a recent outing with Utah Falconers Association Vice President Krista Edwards and her falconry mentor Herald Clark, Edwards recalled one of her falcons being hunted by a golden eagle while hunting. Clark gave her another peregrine falcon as a gift, as the law prevented the wild-caught bird from being sold to her.

This mentoring relationship is both a solid tradition and part of Utah law. An apprentice falconer must be sponsored by a general or master falconer to ensure that their training and the care of their bird is adequate.

Edwards, a Utah teacher, had long been fascinated by birds in general and reached out to another Utah woman who was posting about falconry on Facebook. When Edwards met her and her falcon, she was smitten.

In addition to using birds of prey for hunting, Edwards is a licensed falconry instructor and is home to birds that cannot be returned to the wild and uses them for a variety of educational purposes. Many falconers learn the craft of making their own hoods, leashes and jesses — the leather thongs attached to a bird’s legs that allow them to be held with a gloved hand — and Clark says Edwards is adept at the craft.

For Clark, attending a convention at Olympus Middle School was his introduction to falconry.

He recalled: “A gentleman – I was in 7th or 8th grade – brought some raptors and he flew a red-tailed hawk over the crowd and it flew right over my head. I knew I had to do this one day. “

At the age of 21, Clark met falconers in Utah and was mentored by a well known falconer and author named Ricardo Velarde. Clark originally kept Falcons for less than a decade, and instead a career in dentistry and raising a family became his priorities.

Since returning to the sport, Clark has been passing on his knowledge to others as a mentor.

A modern hunt

Clark was flying an arctic gyrfalcon that day in addition to his and Edward’s peregrine falcons, hunting high in the air. Their vision is up to eight times better than ours, and hawks — capable of horizontal flight at 40-60mph — can swoop down on prey at upwards of 200mph, according to Clark.

Avian flu outbreaks in Utah mean falconers will not allow their raptors to hunt wild birds this year. The falconers brought live doves for the hunt and the falcons had a 50% success rate that day, with one dove left free to remain in the wild.

Hawks, on the other hand, as a recent outing with Craig Boren has shown, hunt from the air or from a perched position, and typically from much lower altitudes than hawks. Unlike hawks, which prefer to catch their prey in flight, hawks track their prey on the ground.

Boren is the President of the Utah Falconers Association and his two Harris’ Hawks can hunt alone or in a team. According to Boren, Harris hawks are known as the wolves of the sky, hunting together in groups.

Normally a desert species living in the American Southwest and Mexico, the hawks have adapted well to the Utah climate and have heated winter quarters at Boren’s Utah home.

A trip with a falconer starts with attaching GPS telemetry technology that allows a falconer not only to track a bird in case it flies away, but also to get everything about the trip, including the bird’s trajectory, altitude and speeds using a smartphone app.

Borens Harris’ falcon, Stella, relied on our group as their hunting team. While we walked through snowy undergrowth to rouse rabbits, Stella rode a light and tall perch supported by bores, giving her a clear view from above.

“They have a lot of variety in their diet,” Boren explained. “Hawks can break down and digest bones, fur, feathers, teeth and even claws; they cannot eat only meat to get the full nutrition they need.”

While Stella trailed rabbits three times that day, she failed to catch any. Boren explained that older late-season rabbits are often adept at evading capture. Rabbit populations in Utah have also declined due to drought and disease outbreaks.

A 17-year-old aspiring falconer and his father were present at Boren’s that day. They had spent time with falconers and were looking for a sponsor. Trainees must spend two years with a mentor, and it can take eight years or more to become a master falconer in Utah, according to Norvell.

Falconry is a sport with a rich history, a shared bond between passionate falconers and their birds, and serious time commitments.